Recently, a large U.S. company executed a sizable portfolio of cross-currency derivatives to hedge its international exposure. As it evaluated prospective swaps trading partners, the company—let's call it XYZ Corp.—was surprised by both the size and the variance in credit-charge markups proposed by the different banks. It was also concerned about the significant credit risk posed by some of the banks and was unsure how best to manage this exposure.

Recently, a large U.S. company executed a sizable portfolio of cross-currency derivatives to hedge its international exposure. As it evaluated prospective swaps trading partners, the company—let's call it XYZ Corp.—was surprised by both the size and the variance in credit-charge markups proposed by the different banks. It was also concerned about the significant credit risk posed by some of the banks and was unsure how best to manage this exposure.

When XYZ had executed derivatives trades in the past, counterparty risk was not top-of-mind. Its discussions with banks typically focused on two topics: market rates and how much markup the banks would add to the market rates to compensate for XYZ's credit risk and provide a return on capital. XYZ would typically compare the markups among its stable of swaps banks and award each trade to the lowest-cost provider.

On the surface, this approach appeared to help XYZ select the provider with the lowest price, but it had two critical flaws. First, it ignored the providers' relative credit quality; the company treated all counterparties as equal. Over the past several years, XYZ has begun to pay more attention to the counterparty risks posed by its banks, and in deciding which bank to award its current swaps business, the company wanted to take the banks' credit profiles into consideration as it weighed their pricing differences. Second, XYZ's former approach to evaluating swaps providers gave the banks the opportunity to show a competitive credit markup to win the trade, with the intent of making additional profit by showing a less attractive “market rate” than might be available elsewhere in the market.

XYZ managers decided that they needed a new approach to quantifying and pricing counterparty risk. They wanted to select hedge providers based on each provider's all-in costs, including the bank's risk of default. They wanted to have better control over the pricing discussion to ensure that they received the best possible market price. And they wanted to continue managing their credit exposure to those providers for the entire life of the swaps.

Companies Refocus on Counterparty Risk

The shift in XYZ's attitude toward credit exposure to its swaps dealers reflects a broader trend. Most companies are now paying more attention to their banks' credit quality than they did a decade ago. The financial crisis highlighted the risks of default by a hedge counterparty. Banks' credit ratings have been downgraded, which has reduced or eliminated the ratings differential between banks and corporations. And bank credit spreads have widened relative to corporate spreads, reflecting the market's view of increased risk of a bank default.

At the same time, companies are facing a material increase in the credit-charge markups for certain trades, as well as greater pricing differences among banks. Market forces are driving some of this change. Increased volatility in the currency and interest rate markets, along with the skewed risk profiles that result from today's historically low interest rates, have increased the potential credit risk for trades such as cross-currency or interest rate derivatives. This increased exposure for banks has, in turn, led to an increase in credit charges. Costs have also been influenced by higher spreads on credit default swaps (CDS), banks' ongoing refinement of credit-pricing methodologies, and increases in bank capital requirements that are complex and inconsistently applied. As a result of all these developments, many companies have recognized that counterparty risk is not a one-way street in derivatives trades, and that they need to actively manage their trading relationships from both a pricing and a counterparty risk management perspective.

At the same time, companies are facing a material increase in the credit-charge markups for certain trades, as well as greater pricing differences among banks. Market forces are driving some of this change. Increased volatility in the currency and interest rate markets, along with the skewed risk profiles that result from today's historically low interest rates, have increased the potential credit risk for trades such as cross-currency or interest rate derivatives. This increased exposure for banks has, in turn, led to an increase in credit charges. Costs have also been influenced by higher spreads on credit default swaps (CDS), banks' ongoing refinement of credit-pricing methodologies, and increases in bank capital requirements that are complex and inconsistently applied. As a result of all these developments, many companies have recognized that counterparty risk is not a one-way street in derivatives trades, and that they need to actively manage their trading relationships from both a pricing and a counterparty risk management perspective.

Historically, most companies used a fairly standard process to evaluate and manage their exposure to banks' credit risk. They would set exposure limits for each counterparty based on credit quality. They would allocate trades among counterparties to avoid concentrated exposure, giving preferential pricing to certain banks in order to diversify their portfolio. The more sophisticated companies would track each bank's credit ratings and CDS level, and might include provisions in their trading documents that allowed for early termination if the bank's credit rating changed significantly.

In theory, if default by a bank counterparty became more likely, this process would enable the company to take action to reduce its risk. However, its efficacy is limited. First, as the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy illustrates, corporations cannot always act quickly enough to mitigate counterparty risk, even if they recognize an impending default. Second, this process does not address credit pricing inconsistencies, nor does it provide the company with a way to compare banks' prices on an apples-to-apples basis.

Because of these deficiencies, this straightforward approach may be appropriate only for companies with limited exposures—for example, companies with hedges such as rate locks or foreign exchange (FX) trades that are shorter than one year, where counterparty risk and credit charges are low. Companies that have larger exposures, either as a result of longer tenors or large notional amounts, should consider a more robust approach.

Professional Market Approaches

Banks and other professional derivatives traders mitigate counterparty risk using two different approaches. When working with smaller financial services counterparties or corporate clients, many use sophisticated models that they've developed to evaluate and price risk. These models typically take into consideration the bank's potential credit exposure to the counterparty under the proposed trade and the impact of the trade on the bank's overall derivatives portfolio with that counterparty. They use a number of inputs: the terms of the proposed trade; the credit terms of the bank's ISDA master agreement with the counterparty; an inventory of all existing trades between the two counterparties, including terms and current mark-to-market (MTM) value; and credit spreads for the counterparty, using the company's CDS or an index

A bank uses its model to run simulations on a portfolio of trades under a variety of market scenarios. Then the bank uses the results of these simulations to calculate its potential exposure to the counterparty over the lifetime of the trades. This type of model can calculate credit charges for a proposed trade based on the trade's marginal impact on the firm's overall risk position. Once the trade is executed, the bank can use the model's risk outputs to construct an appropriate credit hedge using credit default swaps, though in many cases the bank relies on diversity within its counterparty risk book to neutralize its exposure.

A few companies that engage in derivatives trades have taken a cue from the banks and attempted to replicate the professional traders' models to calculate the cost of their banks' counterparty risk. This enables them to adjust each bank's proposed credit charge to account for the company's cost of taking on credit exposure to that bank. However, companies face several substantial obstacles to using bank-style modeling. First, the underlying models are complex; developing and maintaining them requires a significant investment in technology and analytical resources. Second, once a company has a model, it needs to allocate resources to analyze the impact of each planned derivatives trade with every potential counterparty, to determine the appropriate credit-charge adjustment per counterparty. This could result in several hours of work per proposed transaction, depending on the number of potential counterparties and scenarios the company wishes to evaluate. Finally, a company's derivatives counterparty exposure is typically concentrated within the bank sector, limiting any benefits from diversification. As a result, companies using this approach must continue to dedicate resources to ongoing monitoring and management of their credit exposure to each individual bank.

Banks have historically found the modeling approach too complex and time-consuming to use for all counterparties. Furthermore, the amount of counterparty risk to be managed by the banks could exceed regulatory limits for certain counterparties, particularly those with whom they transact in a market-making capacity, such as other dealers or institutional investors.

In these situations, banks and their professional counterparties manage risk using bilateral collateral arrangements, which are similar to margin requirements on an exchange. Notably, the Dodd-Frank Act imposes margin requirements on most derivatives activity, which will result in near-universal adoption of this approach by professional counterparties in the not-too-distant future.

These arrangements typically involve daily posting of margin equal to the net MTM value of each firm's portfolio of trades with each of its counterparties. Margin is typically held either by the party to which it was posted or by a third-party custodian or clearinghouse, depending on the terms of the collateral agreement. This collateral effectively neutralizes counterparty exposure for these trades, creating an environment in which market makers can offer a single market price that is available to all margined counterparties, without the need to adjust for credit charges or worry about credit capacity limits.

Pros and Cons of Margining

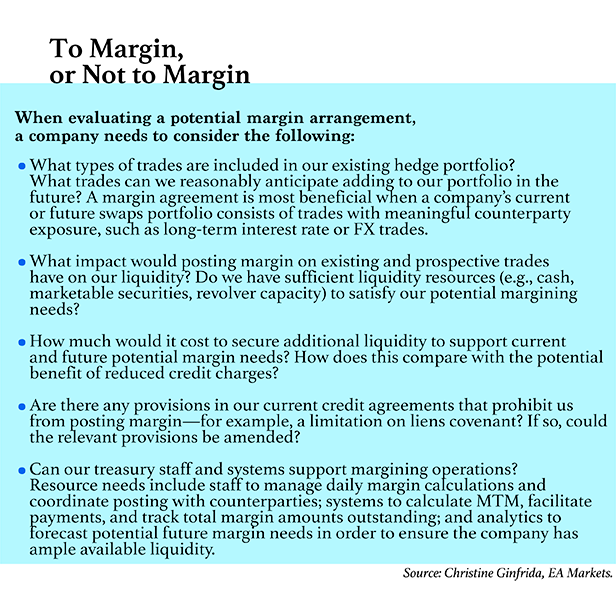

Some companies, particularly those that find the modeling approach burdensome, may wish to consider collateral arrangements. Incorporating margin requirements into derivatives trading documentation enables a company to reduce its counterparty credit exposure, and it creates a level playing field among prospective bank counterparties. This means the company doesn't need to assess each bank's credit risk and then weigh its proposed markups in light of that exposure. In fact, margin requirements have the potential to eliminate banks' credit charges altogether.

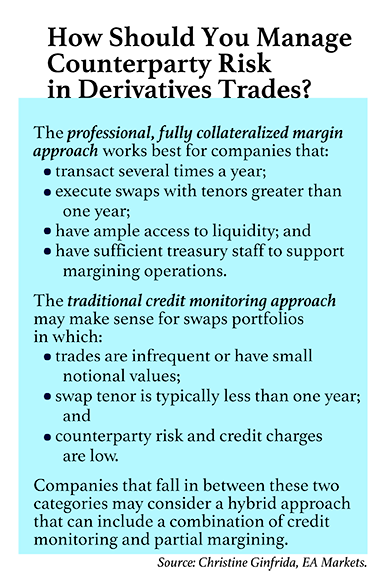

The obvious downside of placing margin requirements on derivatives trades is that cash becomes tied up as collateral in support of the trades. A company following the professional margining model must not only commit collateral equivalent to the initial market value of the trade, but must also be ready to increase or decrease the collateral on a daily basis to reflect changes in the derivatives' value. An MTM-based collateral arrangement may result in significant capital calls arising from changes in market rates that are beyond the company's control. This risk is likely to concern companies that are unaccustomed to such swings in funding requirements. Managing margin also places added operational demands on the treasury function. As a result of these considerations, an MTM-based margin arrangement is best suited to companies that transact several times a year, execute swaps with tenors greater than one year, have ample access to liquidity, and have sufficient treasury staff to support margining operations.

To address operational and liquidity concerns, companies may prefer to adopt margin provisions that strike a balance between mitigating risks and substantially increasing demands on the treasury function—in essence, moving from a “fully collateralized” trading relationship to one that is partially collateralized. For example, a company and its counterparty may agree to a margin threshold, which would eliminate the need by either party to post margin until the MTM value of the company's swaps portfolio with that counterparty exceeds a predetermined value. Or the company and its counterparty may agree to assess margin requirements on a weekly basis, instead of daily, which reduces by 80 percent the amount of time spent managing margin, though this approach would expose the company and its counterparty to more meaningful swings in MTM between valuation dates.

By modifying the terms of a fully collateralized margin agreement, a company would forgo some of the credit protection and potential pricing benefits of a fully margined agreement in exchange for reducing the operational or liquidity burden that margining places on the organization. Companies can also manage margin needs through careful distribution of transactions among their counterparties.

Credit Where Credit Is Due

At the end of the day, there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution for companies seeking to manage bank counterparty exposure. The vast majority of companies continue to use a traditional credit-monitoring approach to mitigate counterparty risk in derivatives trading. The use of either a modeling or margining approach is growing, however, with some of the largest multinational firms leading the charge. And while regulators do not currently impose margin requirements on corporate end users of derivatives, companies may soon find that some banks won't offer certain types of trades, such as long-dated FX transactions, if their counterparty refuses to post margin. This is because Basel III capital rules require banks to allocate large amounts of risk capital to these types of trades if they're transacted on an unmargined basis.

Companies can reap substantial rewards using margining in derivatives trades, even if margin isn't required. This is the path that XYZ Corp. pursued. That company determined that the up-front reduction in credit charges—which accounted for tens of millions of dollars over the life of the trades—would more than offset the potential cost of increased liquidity, while addressing the company's risk management concerns.

Companies can reap substantial rewards using margining in derivatives trades, even if margin isn't required. This is the path that XYZ Corp. pursued. That company determined that the up-front reduction in credit charges—which accounted for tens of millions of dollars over the life of the trades—would more than offset the potential cost of increased liquidity, while addressing the company's risk management concerns.

An organization that implements a margin agreement, particularly a fully margined trading document, regains control of the pricing discussion. No longer does the bank's markup for credit, or the company's desire to diversify bank counterparty risk, drive its selection of hedge providers. As XYZ found, companies with margining agreements can award trades to the banks offering the best market price.

End users need to carefully consider all available tools for managing counterparty risk and select the approach that best suits their needs. Whichever approach a business chooses, it should only give credit where credit is due, and ensure it gets credit in return.

—————————-

Christine Ginfrida is a director of advisory services for EA Markets LLC, a corporate finance and capital markets advisory firm based in New York City. Ginfrida has more than 15 years of experience in structured products origination and derivatives marketing. She has previously worked for Citigroup, JPMorgan, and Merrill Lynch providing interest rate, currency, and credit risk management advisory services.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.