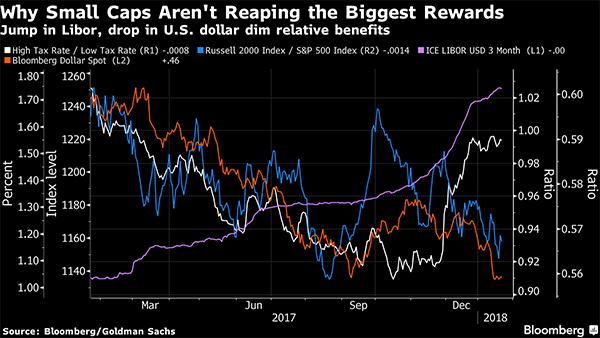

First, the London interbank offered rate (commonly known as Libor) is going up. And second, the dollar's been going down.

Until mid-October, the relative performance of the Russell 2000 Index versus the S&P 500 Index loosely tracked the ratio of a basket of high-tax stocks compiled by Goldman Sachs versus their lower-tax peers. It made sense: Smaller firms tend to be more domestically focused than their larger-cap peers, and as such, were poised to benefit more from a decline in the U.S. corporate rate.

But around that time, three-month Libor costs started to surge, and ended up gaining 40 basis points in a little over three months. Soon thereafter, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index headed south, and proceeded to sink to its lowest level since the start of 2015 earlier this month.

Recommended For You

Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer of Bleakley Financial Group, on Monday flagged research showing more than 40 percent of debt issued by Russell 2000 companies is floating and therefore susceptible to the rise in the benchmark rate. Although some of these firms have made use of derivatives to effectively convert floating-rate into fixed obligations, they're still more interest-rate sensitive than their larger counterparts that have embarked on a bond-issuance frenzy in recent years. In addition, bigger companies tend to get a tailwind from a weakening greenback, as a higher share of their profits are earned overseas compared to small companies.

From: Bloomberg

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.