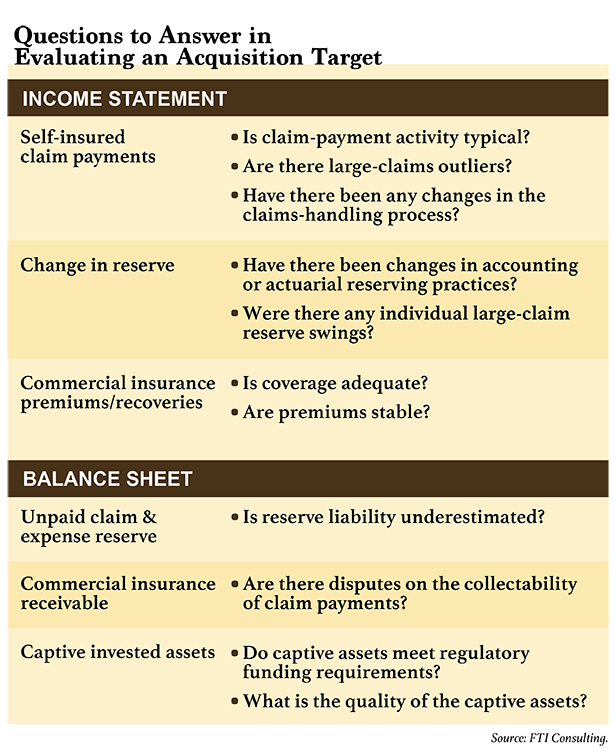

1. Understated Claim Reserve Liability

Risk 2: Changes in Reserving Practice

Risk 3: Large-Claim Volatility

Risk 4: Inadequate Captive Funding

Following a Transaction

- Gauge the combined company's risk appetite. Post-acquisition, the combined company will be larger and likely more diverse. Thus, it may be smart to raise the newly combined company's self-insured retention or insurance limits. Working with an actuary or a broker to explore the best coverage options will help the newly formed company determine its optimal retention levels.

- Expedite systems integration. After a merger or acquisition, the new organization will need to determine how to handle claims and manage risks as one company. It's not uncommon for two claim systems to run concurrently during a transition period, but the company will want to develop best practices over time to eliminate redundancies. Bringing in a third party can help expedite the process.

- Consider unwinding the captive. The merged company may want to consider consolidating the target's captive into its own or running off the existing claims. Consolidation generally reduces costs; running multiple captives at once would be costly. Also, as there are fewer claims left outstanding, the ratio of variable claims payments to fixed captive overhead expense makes running a separate captive less and less attractive. Because existing claims could take years to run off, the company may want to perform a loss-portfolio transfer of the remaining outstanding claims.

Jim Toole is a managing director at FTI Consulting, where he leads the life and health actuarial team in the Global Insurance Services practice. He is also a contributor to FTI Journal . Toole has more than 25 years of management and technical experience in the life, health, P&C, and captive-insurance industries, including a variety of roles leading consulting firms and insurance companies.

Jim Toole is a managing director at FTI Consulting, where he leads the life and health actuarial team in the Global Insurance Services practice. He is also a contributor to FTI Journal . Toole has more than 25 years of management and technical experience in the life, health, P&C, and captive-insurance industries, including a variety of roles leading consulting firms and insurance companies.  Robert Stewart is a director at FTI Consulting in the Global Insurance Services practice, and is also a contributor to FTI Journal . He is a credentialed property-casualty actuary with more than 10 years of insurance and reinsurance experience.

Robert Stewart is a director at FTI Consulting in the Global Insurance Services practice, and is also a contributor to FTI Journal . He is a credentialed property-casualty actuary with more than 10 years of insurance and reinsurance experience.NOT FOR REPRINT

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.