The world's biggest asset managers are lobbying for a last-minute reprieve from a European Union (EU) policy that could throw about 80 billion euros (US$94 billion) of money funds into turmoil.

BlackRock Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co., and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. are among giants hoping to persuade EU authorities to preserve a key feature that investors have come to expect: the fixed share price. Public statements by regulators so far suggest that new rules that start on Jan. 21 will eliminate the ability of such funds to maintain the stable value, eroding the main appeal of such products.

Corporate treasurers around the world rely on money funds to park their cash with the assurance they'll be able to take out every dollar—or euro—when they need funds for payroll or investments. The new rules leave investors with even fewer safe places to stash their money, as many banks are reluctant to accept large cash balances, while deposit rates in the region are expected to stay below zero for at least another year. Floating-rate funds aren't a great alternative, especially for treasurers, because it would create tax and accounting headaches.

Recommended For You

“We are now at the mercy of the passage of time,” Alastair Sewell, head of fund and asset manager ratings EMEA and Asia-Pacific at Fitch Ratings, said in an interview. “With the reform deadline drawing ever closer, regulators and national authorities will start needing to make decisions to define what happens.”

If EU authorities don't reverse their stance, fund companies have warned that the policy could mean the death of stable-price euro funds, as managers are forced to offer floating-rate funds or investors turn away from the fund industry altogether and move their money to banks. Peter Crane, founder Massachusetts-based research firm Crane Data LLC, said he expects half of the roughly 80 billion euros in investments to wind up at variable net-asset value funds and the other half at banks.

The latter option is especially unpalatable to fund companies, who've enjoyed steady growth in assets of constant-value products in the past decade. Euro-denominated funds account for just over 11 percent of a roughly 700 billion-euro industry for constant-value funds, with the remainder based in dollars and pounds, according to data from iMoneyNet. BlackRock, JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs operate the biggest euro-denominated money-market funds that maintain a fixed share price.

Until the Reserve Primary Fund broke the buck in the U.S. during the 2008 financial crisis and spread panic through the financial industry, money-market funds were considered among the most predictable and safe investments around. The collapse spurred regulators, first in the U.S. and then in the EU, to adopt protections for investors to make sure they can easily get their money back.

While the industry fended off the most draconian proposals in both regions, the restrictions have still had a major impact in how the industry is structured. U.S. investors showed their preference for fixed share price funds by yanking hundreds of billions of dollars from funds that had to float their shares for the first time.

ESMA Bombshell

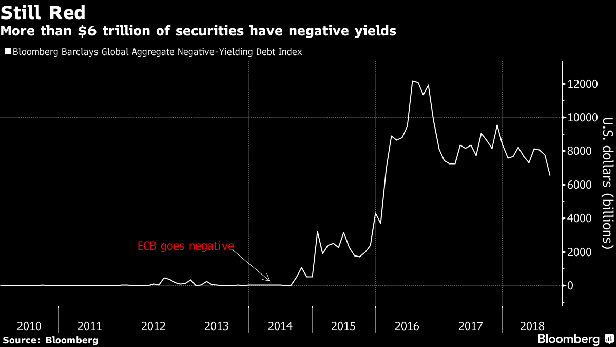

At issue now is how the new rules affect a system the industry devised in 2014, when the European Central Bank (ECB) drove one of its main rates below zero in the aftermath of a debt crisis that triggered negative yields on securities generally favored by money funds.

Money funds traditionally accrue income and distribute it to investors in the form of additional fund shares. Each share retains the fixed price. On days when income is negative, the industry has relied on a newer tool called the reverse distribution mechanism, which works in the opposite direction by reducing the number of shares an investor has in a fund while each remaining share keeps the fixed price.

The industry was caught by surprise last year when the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published technical standards for the implementation of the new rules. Buried in paragraph 186 of the 162-page document, ESMA had a bombshell: its view that the industry's share cancellation practice would be prohibited under the upcoming regulation.

The industry's biggest lobbying groups swung into action with opposition letters, with groups representing money-market funds and asset managers telling the regulator that the practice is widely used and approved by national regulators, including in Luxembourg, a major hub for the fund industry. ESMA was misguided in its approach, according to the groups whose members include the asset-management units of JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and others.

But the industry faced another setback in January when the European Commission, the EU's executive arm, supported ESMA. The commission's lawyers wrote a private memo supporting their position, which was shared with a select number of industry players but never released officially. It was later disclosed under a freedom of information request.

ESMA has asked the commission to disclose the memo publicly to help clarify matters. A representative for the commission said it has provided the memo to people who requested access to it. The Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, Luxembourg's financial regulator, had approved the mechanism and is now monitoring the discussion between ESMA and the commission, according to a spokeswoman.

European Parliament lawmakers who drafted the underlying legislation say the regulatory statements are out of step with their intent following three years worth of debate. Politicians led by Neena Gill, the primary lawmaker responsible for the legislation, said earlier this year it wouldn't be good practice “to change a highly contested regulation without following the appropriate procedures a few months before its entry into application.”

Less than four months before the regulation kicks in, the industry remains in a lurch as it explores viable alternatives. While interest rates are increasing in the U.S. and U.K., the ECB's deposit rate is still below zero.

BlackRock, the world's biggest asset manager, has said the regulator's stance was “concerning,” and that it would be “impractical” to prohibit the practice. Without an alternative mechanism, BlackRock says, constant net-asset value funds “will be operationally unmanageable.”

From: Bloomberg

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.