U.S. corporations have largely abandoned the contentious deals that allowed them to shift their addresses abroad for a lower tax rate. Yet a key part of the transactions is continuing quietly even after President Donald Trump's tax overhaul.

The 2017 tax law was designed to stop traditional inversions, which had brought scrutiny and negative publicity for companies that moved their headquarters overseas, as well as to halt the flow of valuable intellectual property (IP) to low-tax countries. For companies that invert, the address change is generally the final step so they can more easily access the cash they've generated after years of shifting IP overseas.

Most firms are continuing with business as usual when it comes to their IP since the law's provisions aren't enticing enough for them to keep it at home, according to interviews with eight tax experts who advise large public corporations. They disclosed the details of the conversations they're having with companies, but declined to identify the specific clients.

Recommended For You

The problem: Such IP moves mean that other countries ultimately get to collect the billions of dollars of tax revenue generated by many U.S.-made innovations, including life-saving drugs, the algorithms that power social media networks, and the software running computers and smartphones.

“It's not changed the kinds of tax planning we've talked about for 20 or 30 years,” says Linda Pfatteicher, managing partner of law firm Squire Patton Boggs' San Francisco and Palo Alto offices. “The changes just tweak around the edges.”

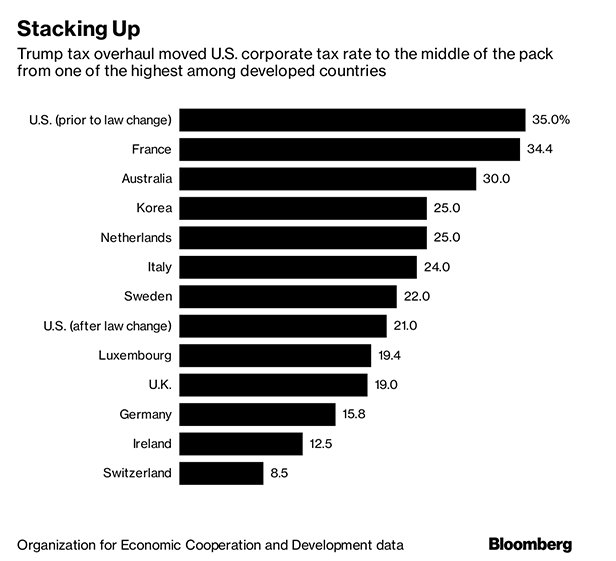

That's a blow to Republicans' plans, which had intended for the law's corporate rate cut and overhaul of international tax rules to remove the incentives to shift IP abroad and invert. The U.S. now has a corporate rate of 21 percent, lower than the previous 35 percent but still pretty average when compared with other countries with developed economies. And it's high relative to the 12.5 percent rate in Ireland, a popular destination.

'Still Beneficial'

For years, U.S. companies, especially in the technology and pharmaceutical industries, have shifted patents and software to subsidiaries in low- or no-tax countries, and paid the foreign firms licensing fees to use the assets. Those franchise fees and royalty payments were booked as income offshore and taxed at the other country's lower rate. A change in headquarters was the choice for the most tax-averse companies. The 2017 tax law was supposed to change all that.

The law attempts to deter profit shifting and make sure companies are paying a minimum amount of tax in the countries where they store their IP. If the offshore tax rate is at least 13.125 percent, the company isn't supposed to owe anything to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. If it's below that rate, in most cases the company will owe only a couple of additional percentage points to the United States, in what's called the GILTI tax—still below the 21 percent it would pay if those assets were in the U.S.

For example, U.S. corporations in Ireland would pay about an additional half a percent to the IRS. “The raw math is still beneficial to move that out of the U.S.,” says Albert Liguori, a managing director with consulting firm Alvarez & Marsal. “There's a concern that once you come into the U.S., you can't get it out.”

Shifting IP, rather than headquarters, is also a strategic political move, says Robert Willens, an independent tax consultant. A true inversion entails merging with a foreign firm and generally requires disclosures—but shifting IP doesn't involve the same scrutiny and can happen quietly, shielded from finger-wagging by U.S. lawmakers or the president.

Both parties have railed against inversions, and ending the practice is probably one of the few things former President Barack Obama and Trump agree on. Obama called the moves “unpatriotic,” and Trump has said he's “disgusted” with them.

Many other countries with lower corporate rates have an additional source of tax revenue, such as a value-added tax (VAT), so they can afford to keep rates low. The U.S. doesn't have a VAT and likely won't as long as Republicans control Congress because it's viewed as a tax increase.

Unless tax writers can get the corporate rate into the mid to low teens (which would require finding additional revenue or adding trillions more dollars to the budget deficit), companies will continue to shift their easiest-to-move assets like IP to countries where it's the least expensive to keep them, tax experts say.

Unknown IP Locations

Researchers at the U.S. Commerce Department's Bureau of Economic Analysis seem to agree. “Although the ultimate effects of the 2017 changes to U.S. tax law remain to be seen, there is reason to believe that the incentives for this behavior have not disappeared,” they said in an August report, referring to putting IP overseas.

It's hard to know just how much intellectual property U.S.-based companies hold overseas. Corporate filings show few details about where such property is located, and companies are hesitant to disclose the information for public relations reasons.

For example, Apple Inc.'s filings show where about 3.6 percent of its profits are earned, according to analysis from researchers at the University of Copenhagen and University of California Berkeley. For Alphabet Inc.'s Google, the location of about 1.4 percent of profits is visible, the data shows. And less than 1 percent of Facebook Inc.'s and Nike Inc.'s profits were tied to a specific jurisdiction in their public disclosures.

Apple and Google have said in recent filings that any change in Ireland's tax rates could be material to their financial statements, a sign that they intend to maintain their employee presence and assets there. Apple, Alphabet, Facebook, and Nike declined to comment.

Ireland's National Treasury Management Agency said its own IP numbers have been distorted in recent years because of “on-shoring” by U.S. companies. About 65 percent of the value of the technology produced in Ireland in 2015 was from U.S. owned-companies, a figure that the country said it expects to continue to expand even in the wake of the tax law.

Corporate inversions, like those conducted by Burger King Worldwide Inc., Johnson Controls International Plc, and Medtronic Plc, were a driving force behind the tax overhaul. Under Obama, the Treasury Department issued rules to deter inversions, but the tax law was intended to be the final blow for switching headquarters and IP shifting.

'Stay Put' Decision

To be sure, the tax law has changed the calculus for some corporations. Drug maker Amgen Inc. said in April it would build a manufacturing plant in Rhode Island instead of Puerto Rico. Those are mostly one-offs, though, and tax experts say it's unlikely to see a homecoming of software and patents already parked overseas.

Tax advisers say they were inundated earlier in the year with requests from multinationals about whether some of the tax law changes—such as the GILTI tax and the minimum tax on offshore payments—should prompt them to restructure their businesses and bring IP home.

Most companies decided they didn't want to up-end their tax planning because of uncertainty about how the various provisions of the law would interact and whether a future Democrat-controlled Congress would roll back some provisions of Trump's overhaul.

There's more confidence that lower-tax jurisdictions like Ireland will maintain their corporate tax regimes, according to Tom Zollo, a principal specializing in international tax at accounting firm KPMG.

“After doing some modeling, many have decided to stay put for a while,” Zollo says.

From: Bloomberg

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.