Despite strong incentives in the Republican tax plan for American executives to expand, invest, and ultimately boost the U.S. economy's growth potential, a lot of the debt companies are issuing appears to be motivated by something else.

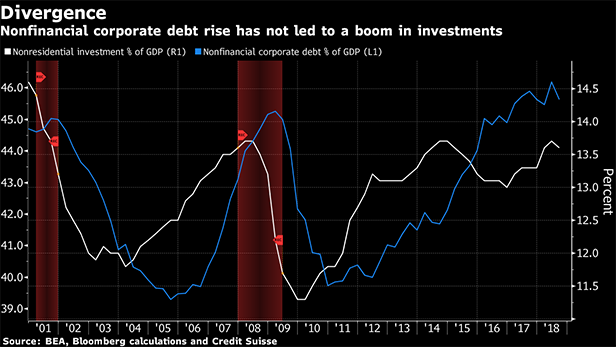

Non-financial corporate debt stands at 45.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), near the highest level in post-war recordkeeping. Despite that, non-residential investment—a broad category in the national accounts that includes everything from office buildings to software—has only been bouncing around the 13 percent of GDP range since 2012.

Recommended For You

“You would think that companies want to add to productivity capacity, but we really haven't seen it,'' says Priya Misra, head of global rates strategy at TD Securities USA. “If they view the economy as in the late stages of the expansion, then there isn't a lot of confidence about the outlook and it is easier to buy back stock.''

It's difficult to trace the uses of money raised from debt through the various accounts in the economy. But one worry is that rising corporate borrowing isn't sustainable if the trend is more about transferring cash to owners rather than investing in assets or innovations that can produce more cash to pay future bills.

“When we think about business cycles and what ends them, you can always follow the leverage,'' says Ellen Zentner, chief U.S. economist at Morgan Stanley & Co. “It is not a household issue this time; it is going to be corporate.''

One corner of the corporate debt markets that's ringing alarms is leveraged lending, or credits to highly indebted companies.

Globally, new issuance hit a record US$788 billion last year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said in a recent blog post, with the U.S. market accounting for more than 70 percent of the total. Credit quality and investor protections have deteriorated, and some of the transactions are arranged specifically to extract cash for shareholders while loading a company's balance sheet with debt. That can reduce management's flexibility in an economic downturn, and forecasters expect U.S. growth to slow over the next two years.

A widening group of financial-market regulators and investors are questioning whether the corporate debt bubble is sustainable, especially leveraged lending. The Office of Financial Research, the U.S. Treasury's financial market watchdog, said “rapid growth in leveraged lending is a concern'' in their annual report to Congress released Nov. 15. Last month, the Fed's senior supervisor in charge of risk surveillance, warned banks of “weakness in risk management.”

Financial Engineering

The IMF's financial stability chief, Tobias Adrian, and his team warned in the blog post that a lot of the debt issuance looks like financial engineering rather than investments in assets that will pay for the debt in the future.

“More than half of this year's total involves money borrowed to fund mergers and acquisitions and leveraged buyouts (LBOs), pay dividends, and buy back shares from investors—in other words, for financial risk-taking rather than plain-vanilla productive investment,” Adrian wrote on November 15.

Debt-financed U.S. merger activity totals $717 billion year-to-date, already ahead of any of the past five years except 2016, when it totaled $861 billion. Total deal count is 495 this year, higher than any of the past five years except for 2017, which which was 547. That in itself is a poor response to the tax stimulus, says Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Barclays Plc.

“Capital investment decisions are multiyear processes that take time to plan build and execute,” he says.

Given that the stimulus is a little less than a year old, it may take more time for investment spending's share of GDP to rise. Still, mergers, share buybacks, and dividends all reveal a preference in the corporate suite for now, Gapen says. “You grow by gaining market share and trying to control input costs and preserving margins because basically your forecast for revenue growth isn't strong,” he says.

Essentially, that's a preliminary thumbs-down vote that the stimulus from the tax cuts will raise the potential for the economy to grow—and that's the problem with the debt bubble, he says. Debt service is going up while the economy isn't generating more dollars to pay for it.

Mergers and acquisitions don't necessarily create new productive assets, either. In some ways, they are a long-run forecast by companies that market share is better bought than obtained through growth or innovation.

From: Bloomberg

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.