The biggest issuers of U.S. corporate bonds are easing up on selling new securities, which could translate to gains for investors holding the debt.

Banks and other financial companies have sold around US$50 billion of bonds so far this year, down more than 40 percent from the same period a year ago. For the largest U.S. banks, the decline has been even steeper—they sold just $12 billion of debt after earnings, about a third of sales at the same point last year.

Debt sales are falling after banks have largely sold enough debt to meet the requirements of a Federal Reserve regulation, and tax cuts have lifted their cash flow, reducing their borrowing needs. Many foreign banks, typically major January issuers, have sat out amid Brexit jitters and rising hedging costs in currency markets. U.S. and foreign financial companies represent about a third of the $5 trillion high-grade bond market.

“Issuance will be more strategic and more opportunistic,” says Robert Smalley, a credit desk analyst at UBS Group AG. While lower issuance from bank holding companies was widely expected in the market, “once you see it in black and white it finally hits home,” he says.

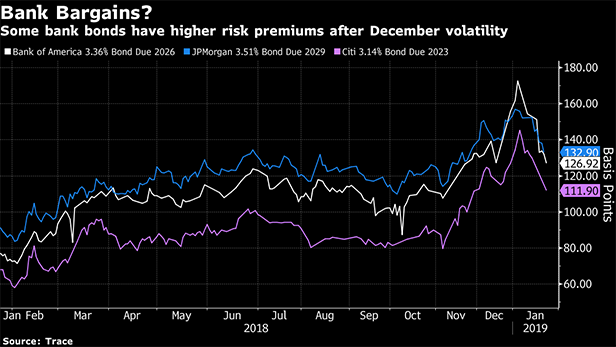

That could translate to gains in bank bonds for the year, at least based on risk premiums, after the securities weakened at the end of 2018. Strategists at research firm CreditSights called the bonds of large U.S. banks a top trade for 2019, thanks to muted new issuance and the lenders' strong balance sheets. Bonds tied to banks returned 1.22 percent through Wednesday, compared with 1.05 percent for broader investment-grade securities.

Banks are just one part of what is likely to be a big slowdown for new corporate bond issuance in 2019, as tax cuts give companies more cash flow to pay down debt. Investment-grade corporate bond sales so far this year have fallen more than 15 percent from the same period last year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Analysts at JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bloomberg Intelligence, and Nomura Holdings forecast that overall issuance this year will fall by about 10 percent. Declining sales of new securities could be one of the biggest near-term tailwinds for a market that faces serious long-term risks, including the fact that around half of outstanding investment-grade debt is in the tier just above junk.

The few banks that have tapped the market have been greeted with fervid investor demand. A $500 million bond from Bank of America for socially beneficial projects sold Tuesday drew 11 times the orders it needed, according to people familiar with the matter. The demand let the lender sell the debt with lower risk premiums than existing bonds. And JPMorgan drew $6.5 billion in orders for a $2 billion unsecured bond sale this week.

Similar hunger for a Morgan Stanley bond last week meant the bank paid a yield just 0.01 percentage point above that of its existing debt for its new securities. The average for this year is closer to 0.12 percentage point.

Declining overall company debt issuance is at least part of why a growing number of strategists at banks including Bank of America Corp., Morgan Stanley, and JPMorgan Chase say it's time to start buying corporate bonds again. A Bank of America survey released this week said that around 38 percent of high-grade investors owned more of the debt than their benchmark indexes in January, about double the proportion in November, because many money managers view the debt as relatively cheap.

Matt Brill, a senior portfolio manager at Invesco, which manages $888 billion, says bank bonds still look like a good buy because most of the securities haven't fully recovered from December's market gyrations. But banks have spent years building their capital levels, and any upcoming slowdown in economic growth won't likely have much impact on lenders' ability to pay their debt obligations, he says.

“There still is value in the banking space,” Brill says. “The credit market has been very strong, and demand for bank paper has been there. Investors have gotten the impression quite early that bank issuance will be underwhelming.”

For years, banks have issued large amounts of debt at their parent companies to meet the requirements of a regulatory rule known as total loss-absorbing capacity, or TLAC. In times of crisis, the parent-company debt would turn into equity to help finance a new, healthy version of the bank. The biggest U.S. banks issued more than $660 billion of this debt between 2015 and 2018, according to Bloomberg data, and have met their requirements.

“With TLAC, the buildup is done,” says Pri de Silva, an analyst at CreditSights. “Banks still need to remain in compliance. They will be regular issuers on and off.”

Now more bank bond issuance is likely to come in shorter-term debt, maturing in three years or less, sold by the operating banking unit, Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Arnold Kakuda wrote in a note on Tuesday. The regulated banks can often borrow cheaper than their holding companies. Overall issuance of dollar-denominated bank bonds are likely to fall again in 2019 after declining 13 percent to $359 billion last year. That, along with banks' healthy capital positions, should help risk premiums on the debt compress, says Jon Curran, a portfolio manager at Aberdeen Standard Investments, which manages about $736 billion.

“They're certainly not giving away these deals,” Curran says. He's been selectively buying bank bonds when he can find value. “It's a nice validation. Banks stand on firm fundamental footing.”

From: Bloomberg

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.