In a Deloitte survey of treasury groups, 52 percent of respondents cited foreign exchange (FX) volatility as their number-one strategic challenge. Meanwhile, a Wells Fargo survey reported that 43 percent of treasury and finance professionals think market volatility, combined with the effects of volatility on hedging decisions and strategy, forms their greatest FX risk management challenge. This comes as little surprise, given trends in currency markets in recent years.

Over the past five years, the trading range of the U.S. dollar vs. many other major currencies has swung widely. Consider, for example, the Brazilian real: BRL220,000 was equivalent to US$100,000 in 2014, but less than US$53,000 in 2018. So a company that earned US$100,000 in real-denominated revenue when exchange rates were favorable would have seen the same revenue devalued to be worth just over US$50,000 when FX rates were at their worst. Businesses with revenues and/or expenses denominated in foreign currencies, such as U.S.-based software companies selling applications in euros in Europe, or U.S. manufacturers using MXN to pay for components they buy in Mexico, are finding it impossible to forecast results or analyze investments with an acceptable level of accuracy.

Leading multinationals have long dealt with currency challenges by implementing sophisticated FX risk management strategies. These companies may be hedging 20 currencies at a time, placing thousands of derivatives trades each year. Their risk management processes are effective, but they're possible only because of the sheer scale of the organization. The advanced technologies these organizations rely on represent a significant investment in terms of both dollars spent and staff resources required for implementation and ongoing management.

The thousands of small to midsize businesses (SMBs) racing toward globalization each year do not have access to the same FX risk management capabilities that multinationals employ. Once they arrive in the international marketplace, SMBs are confronted by the impact of foreign currencies on their sales, procurement, investment, and capital-raising activities. They don't require solutions that are as complex as a multinational's, but SMBs do need to address FX risk up front. And there's a lot they can learn from the well-established currency programs at larger businesses.

Smart SMB treasury groups develop their own, customized version of multinational FX risk management strategies, incorporating relevant best practices on a scale that makes sense for their organization. In building their own approach to currency risk management, SMBs should focus on three goals:

- Defining specific, consistent objectives,

- Understanding and prioritizing exposure types, and

- Implementing a common workflow with practices tailored to corporate objectives.

How to Effectively Define the Program's Objectives

A company's FX risk objectives should be consistent with its financial and competitive objectives. For instance, a technology company that is going global might be relatively young, so its investors may be focused primarily on top-line growth. In contrast, a mature company entering its first overseas expansion might be evaluated mostly on operating margins or net income. And a highly leveraged business or a regulated financial institution is likely most concerned about how FX impacts its leverage, liquidity, and capital ratios.

Organizations that are newly launching global operations should select one or two specific desired outcomes for their currency risk management. Then, they should use these desired outcomes to set the objectives for their currency risk management program and to build the foundation on which they develop the program.

The FX objectives that an SMB selects should reflect core drivers of its organizational well-being. They should also be specific, practical, relevant, and efficient. Avoid vague statements such as “We seek to mitigate the impact of FX on our financial results.” Generality causes confusion and allows room for disagreement about whether an objective is met. For example, the board may take a dim view of a 5 cent-per-share FX loss, while treasury views that outcome as a success because the hedging strategy mitigated what would otherwise have been a loss of 9 cents per share. To avoid this type of situation, the objectives of an FX risk management program need to clearly state what stakeholders expect.

Here's one example of an effective objective: “An unfavorable FX impact is a deterioration in earnings-per-share contribution of recurring foreign-currency revenues and expenses as a result of FX movement. We aim to contain unfavorable FX impact on earnings to US$0.02 per share year-on-year. We will execute our strategy to deliver this result 95 percent of the time.” Obviously, this is an ambitious goal. However, the statement itself is specific and easily understood.

Setting clear, measurable objectives enables the treasury department to:

- Articulate the processes, activities, and support required to achieve each objective;

- Rationalize the value of objectives against the investment required to achieve them; and

- Build performance reports that identify success—or failure—and therefore any necessary modifications to policies or processes.

Although initial objectives might be clear and achievable, they can easily unravel with flawed performance benchmarks. In particular, take care not to introduce bad tactical objectives to good strategic objectives—for example, setting FX rates in the budget that are unobtainable given current market conditions and existing hedge rates.

Companies use budget rates to convert forecast amounts to their reporting currency. Suppose Company X has a sales forecast of EUR1 million that it converts to US$1.2 million in its corporate financial plans based on a budget rate of EUR-USD1.20. Perhaps the company used its bank forecasts to set the budget rate, which is a poor practice but quite common. If Company X has not executed any hedges at 1.20 or better, and the market rate for hedgeing forecast exposures is lower than 1.20, risk managers face an irreconcilable problem that leaves them helpless to deliver a predictable outcome at a rate that achieves the budgeted performance in their reporting currency.

How to Understand and Prioritize Exposure Types

Companies view FX risk through the lens of their functional currency. So, an organization that uses the euro for financial reporting takes on FX risk anytime it engages in revenue- or expense-generating activities denominated in a currency other than the euro.

To optimize their FX strategy, organizations that do cross-border business need to identify which exposure types have the greatest impact on their specific financial objectives. Then they should limit their strategy's scope in order to control the impact of those exposures. Strategies typically congregate around these prominent sources of exposure:

- Transaction—forecast exposure. FX swings can reduce the functional-currency value of forecasted foreign-currency revenues or increase the value of anticipated costs for transactions that will be conducted outside of the organization's functional currency but that are not currently reflected on corporate financial statements.

- Transaction—balance-sheet exposure. Exchange rate volatility can also lead to losses on the corporate balance sheet related to monetary assets or liabilities denominated in a foreign currency, when the value of those assets or liabilities is converted back to the functional currency.

- Translation—net equity (investment) exposure. Companies that own foreign subsidiaries could face financial losses on their equity balance caused by exchange rate movements.

- Translation—net income exposure. Many global organizations face potential losses due to FX fluctuations as they convert earnings denominated in foreign currencies into the parent company's functional currency.

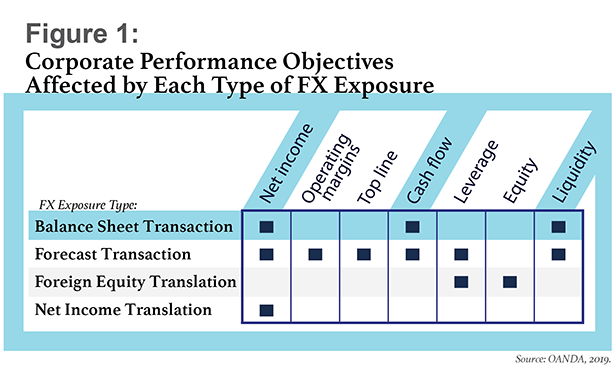

Figure 1 indicates the impact each type of exposure could have on a company's financial objectives, by clarifying the corporate performance metrics that might be affected. For instance, objectives such as net income, cash flow, and liquidity are impacted by balance sheet transaction exposures (as highlighted in blue). Corporate treasury teams can use this information to translate their FX program's objectives into priorities for specific risk-mitigation activities.

Some of these areas are impacted by FX across multiple exposure types. It's worth noting that the impact of the different exposures varies in magnitude. When prioritizing, the treasury team needs to determine not only which exposure types could affect organizational objectives, but also by how much. The source of currency risk that is most top-of-mind, even for treasury, is not necessarily the exposure that poses the largest risk to the company's objectives. Figure 2, below, provides an example.

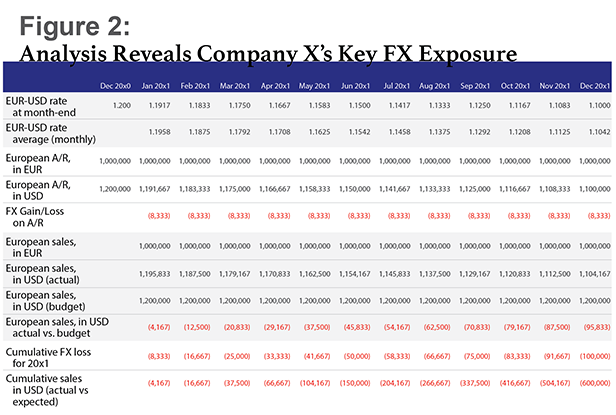

For Company X's finance team, the most obvious FX exposure is the portfolio of accounts receivable (A/R) that is denominated in euros. Because Company X is a U.S.-based business, this A/R balance—along with all other monetary assets that are foreign-currency–denominated—must be re-measured in U.S. dollars for financial reporting purposes. In a year where the EUR-USD exchange rate declines from 1.20 to 1.10, the value of the EUR1 million A/R portfolio declines by US$100,000[1], and the company must record this amount as an FX loss.

But analysis by Company X's treasury team reveals that this isn't the greatest FX risk to the company's economic value. Suppose that the company's average customer payment cycle is one month. The A/R balance of EUR1 million per month implies that the company has EUR1 million in monthly sales. Thus, the company budget anticipates euro-denominated sales of EUR1 million, which rolls up to the USD-denominated corporate budget as US$1.2 million in monthly revenue using the EUR-USD budget rate of 1.20. The decline in the exchange rate to 1.10 would reduce the value of this sales revenue by US$600,000 over the course of the year.[2]

How to Establish an FX Workflow

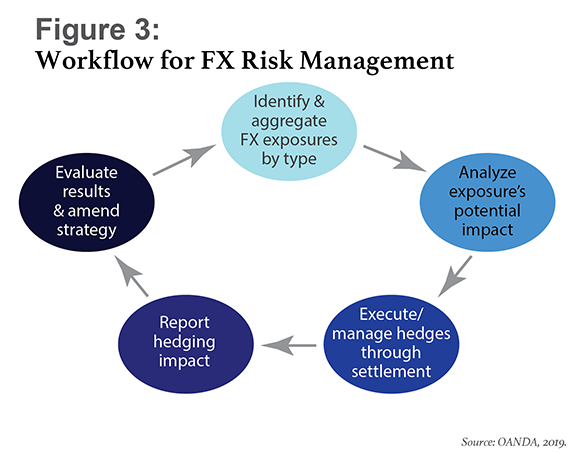

Whatever the scale or complexity of an FX risk management program, success requires that the program feature a robust workflow of activities that act as universal building blocks. (See Figure 3, below.) The workflow must encompass five core steps:

1. Exposure aggregation. Good exposure aggregation requires ready access to the most current data and enables useful analysis for decision support by answering these questions:

- Which currencies are causing exposures?

- How does each exposure impact our financial objectives?

- Which entity is exposed?

- When will each exposure impact corporate financial results?

By aggregating exposure data using this information, companies can analyze the potential magnitude and timing of risk, based on the type of exposure and currency involved.

The starting point and key focus for data aggregation is the exposure type. That's because each exposure type has a unique impact on the company's financial performance, as well as its own unique hedging strategies.

Each exposure type indicates the appropriate data source for that exposure. Understanding where data exists within the company is the first step to successful, accurate aggregation. Some balance-sheet exposures can be found in the enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, treasury management system, or company banking platforms. Other exposures, such as non–functional-currency forecast revenues and expenses, aren't available in most ERP systems, so the treasury team may have to conduct a global survey using spreadsheets, databases, or email to gather forecasts. For organizations with the budget, there are technologies that facilitate a streamlined process in which business units can submit their own dynamic forecast updates when they need to amend data they've submitted.

2. Exposure analysis. There are several ways to produce exposure analyses; the most common approaches include net notional exposure, simulation, and sensitivity analysis. Corporate treasury and finance professionals should be familiar with each of these methods. Other possible approaches include “earnings at risk” or “expected shortfall,” both of which are more complex to compute but provide additional information that treasury staff can use to assess the severity and the probability of losses.

Whichever approach a treasury team chooses, the analysis should break down risks by exposure type, with the goal of pinpointing which exposure types and currencies pose the greatest risk to the organization's objectives. If, for example, the company is primarily concerned with year-on-year variability in earnings per share (EPS) that may result from FX movement, then aggregating and analyzing by exposure type can reveal whether EPS is impacted more by balance-sheet or forecast transactions.

This information, in turn, enables the treasury group to prioritize their hedging strategy. If the analysis shows that forecast exposures have the greatest impact, treasury can net and analyze forecast exposures by currency pair to prioritize which currencies they hedge. Note that whatever approach the company adopts, every analysis must consider net amounts. If the company forecasts EUR1 million in revenue and EUR600,000 in expenses for June 2020, the net FX impact must be calculated based on the net EUR400,000 the business expects to receive that month.

Exposure calculations must also consider the timing of when the transaction—either revenue or expense—will be recorded on the company's financial statements. Timing is crucial in determining the net exposure in each period. Getting the timing right helps ensure that hedges associated with a specific item on the forecast will “settle” (mature) in the same month that the associated revenues or expenses are reported.

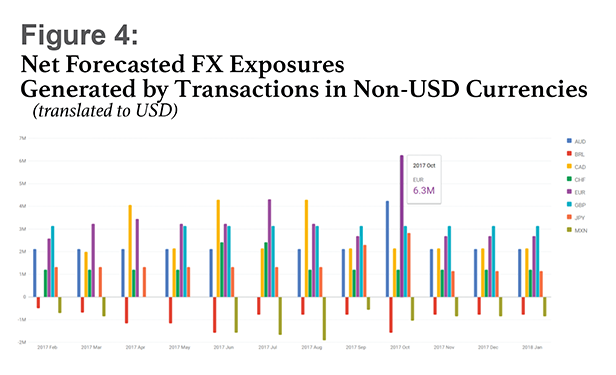

The end result of the processes of aggregating and analyzing exposure data should be to generate a side-by-side analysis by currency for each exposure type. As an example, Figure 4 shows the net forecast exposures of Company Z, broken out by the different currencies in which the company does business.

It's worth noting that a heat-map analysis can also identify the currencies that present the most significant total exposure for a company. However, heat maps do not indicate how or when the organization will be exposed. Instead, they simply draw attention to those currencies that might have the largest overall impact on company value.

3. Hedge execution. Financial markets are complex, sometimes counterintuitive, and opaque. The best approach for executing FX hedge transactions is to keep it simple.

One key to effective execution is to measure everything twice. When implementing a hedging strategy, execution errors—such as using the wrong amount, direction, or currency—can be very costly. Treasury teams can help mitigate this risk by following these protocols:

- Check and recheck the amount, currencies, and exposure direction (receiving or paying) prior to executing a transaction.

- If possible, create a trade authorization process that requires two individuals to review each transaction and confirm that the correct instruments will be executed.

- Most companies don't hedge 100 percent of an exposure, particularly if it is subject to forecasting uncertainty.

Another important policy is to ensure that all hedging decisions are highly disciplined. Many companies make the mistake of trying to predict currency fluctuations. A disciplined, periodic approach—such as hedging a consistent, predetermined portion of the company's exposure each month or quarter—is far more likely to protect against currency-related losses in the long term. Such a systematic FX risk management program helps protect companies against the risk of locking themselves into unfavorable forward rates.

Finally, the treasury team needs to monitor the suitability of their hedges on an ongoing basis. Execution should be continuous, not episodic, and plans should be flexible when exposures change. For instance, forecasts might need to be amended if expectations for organizational performance change—at which point the company will need to re-evaluate its existing hedges.

4. Financial reporting. The financial reporting requirements for hedge accounting were recently simplified by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), but they still require interpretation, rigor, and administration. To manage the complexity of financial reporting for hedges, treasury teams need to simplify their hedging activities. Prioritizing which exposure types and currencies must be hedged to achieve the company's objectives is an important step in that direction. Adopting a robust technology platform that automates and standardizes reporting requirements can also greatly help the goal of simplification.

Treasury and finance teams that need help managing the financial reporting of hedges can seek guidance from a subject matter expert on financial reporting to establish an accurate and concise process for accounting for each type of hedge (i.e., the hedge associated with each FX risk management objective) the company uses.

5. Performance evaluation. The two key elements of evaluating the effectiveness of an FX risk management program are compliance and results. The treasury team should conduct compliance reporting at least monthly to determine whether the strategy is being executed as intended. For example, they should check to ensure that the portion of exposures being hedged falls into the range required by corporate FX risk management policy. (Violations might occur because hedges were poorly executed or misallocated against exposures at the wrong entity, or because exposure forecasts changed causing hedge ratios to fall out of compliance.) They may also need to check compliance with policies around counterparty risk, hedge tenor, instruments utilized, and authorizations. Ideally, the treasury team will be able to see compliance reports in real time so that it's immediately clear whether aggregated exposures are up to date, hedges have been executed in accordance with the company's strategy, and activities are being completed as intended.

It's also important for treasury to report at least quarterly on the results of the hedging program, to identify whether the strategy and execution are meeting the FX risk management program's overall objectives.

When compliance reporting shows that hedges aren't following FX risk management policy, or when results reporting shows that hedges are underperforming in terms of effectiveness at mitigating exposures, treasury can take corrective actions. Compliance reports are most valuable as an alert to oversights, which FX risk managers can easily correct. Results shortcomings might indicate a more serious misalignment between FX objectives and risk management activities.

The Art and Science of FX Risk Management

Establishing a best-practice strategy for FX risk management is both an art and a science. The art lies in matching the right risk management objectives with robust practices that support the company's currency strategy. The science lies in executing those activities reliably and efficiently so that the currency strategy supports overall corporate financial objectives.

Supporting a good strategy with good technology can improve results by increasing efficiency, accuracy, and communication. Companies that adopt appropriate tools are able to do more with less by expanding their risk management activities to address more exposures and currencies, while increasing accuracy and reducing the amount of employee time that FX risk management consumes. The adoption of risk management technology has the added benefit of centralizing and institutionalizing knowledge of the FX risk program. In short, it can reduce the risk of execution errors or information gaps caused by staffing changes.

Chuck Brobst is managing director of the analytics division at OANDA Global Corporation. He is also an adjunct professor of finance at DePaul University in Chicago, where he teaches graduate courses on enterprise risk management and commercial banking. Prior to joining OANDA, Brobst launched a startup in the financial technology space, having previously served as an executive in the global markets divisions of Bank of America Merrill Lynch and ABN AMRO Bank for 15 years.

[1] A/R beginning balance of EUR1 million x budget rate 1.20 = US$1.2 million. A/R ending balance of EUR1 million x actual exchange rate of 1.10 = US$1.1 million. The change is recorded as an FX loss during the year—US$100,000 for the year, US$8,333.33 per month.

[2] The total exposure for the year is EUR12 million in sales. Meanwhile, the average depreciation of euros over the year is US$0.05 per euro—the beginning EUR-USD rate is 1.20, and the average rate over the year is 1.15 [(1.20 + 1.10)/2]. Therefore, the average loss to forecast sales will be EUR12 million x US$0.05, or US$600,000.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.