“This may be the peak before it all falls apart again.”

So said Peter Crane, president of Crane Data, on Monday—the first day of the Crane's Money Fund Symposium, which bills itself as the largest meeting of money-market fund managers and cash investors in the world. He added that he was putting a positive spin on the industry by noting that assets are currently rising in a circumstance when balances typically fall. The amount of money in government and prime funds has soared in 2019 to more than $3 trillion, the most since the financial crisis, driven by U.S. short-term yields exceeding those of longer-maturing bonds.

On its face, the impetus to park money in ultra-safe money-market funds makes a lot of sense. After all, equities are at or near all-time highs, corporate-bond spreads have tightened across the board, and the yield curve is inverted, inevitably raising the specter of a coming recession. In fact, I posited in late March that inversion would most likely accelerate the dash for cash, after noting that during January and February, individual investors bought $39 billion of Treasury bills at auctions, the most since at least 2009.

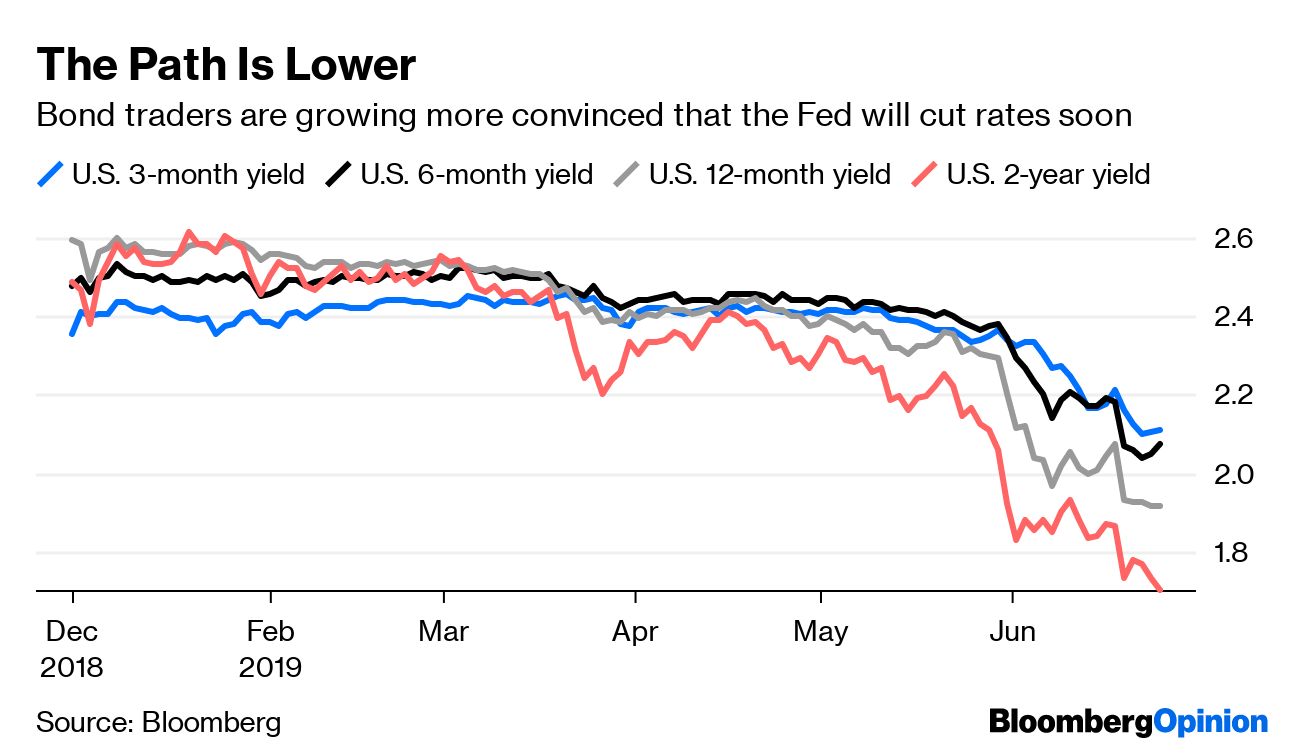

There's one obvious difference between then and now. Three months ago, the Federal Reserve was firmly on pause, with officials signaling they were in no hurry to move interest rates. Now, the bond markets consider a rate cut in July as a virtual certainty and expect the central bank's benchmark lending rate to be about 75 basis points lower by the end of the year.

Make no mistake: Such steep cuts would most likely roil money-market funds. Crane and others at the industry gathering in Boston are putting on brave faces, but the simple truth is that a return to the post-crisis policy of pinning short-term interest rates near zero would force many investors to withdraw their money and seek higher-yielding alternatives.

The problem, of course, is that those other options are few and far between. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Marcus Ashworth recently wrote about the “madness” of 100-year bonds from Austria that may yield 1.2 percent. Bloomberg News's Cameron Crise described the plight of a friend who had plowed money into six-month bills around the start of the year and doesn't know where to invest the principal now that the rate on those Treasuries is some 50 basis points lower. It was 2.38 percent as recently as May 30; it's 2.08 percent now.

It's true that Treasury yields across the board have moved swiftly lower in recent weeks. The benchmark 10-year yield is back below 2 percent. The five-year yield, which reached as high as 3.1 percent last November, is now just 1.72 percent. And this is happening even though the median projection among Fed officials on their “dot plot” is for unchanged rates in 2019 and one cut in 2020.

This divergence in expectations between policymakers and bond traders means the mad grab for yield could only intensify if the Fed follows through with lowering interest rates next month. And if that's the case, investors would be better off leaving money-market funds now in favor of Treasuries with some duration.

Consider the period in 2016 from late January to mid-June, just ahead of the U.K. vote to leave the European Union. In that five-month stretch, the benchmark 10-year yield fell from 2 percent to about 1.5 percent, providing a total return of 5.4 percent. Two-year Treasuries, by contrast, gained just 0.75 percent, and bills (which admittedly had much lower rates at the time) earned only 0.25 percent, according to ICE Bank of America indexes.

That's hardly an unrealistic scenario for the 10-year Treasury note. At their core, longer-term Treasuries are priced based on investor expectations for the path of short-term interest rates. The Fed raised them to a range of 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent, then had to screech to a halt. If they're unlikely to get back to that level in the next decade, and in fact may stay substantially lower for an extended period of time, then a 2 percent 10-year yield looks like a bargain.

Granted, as Crise points out, it would only take 10-year yields rising to 2.23 percent to wipe out an entire year's worth of interest. Still, it's hard to see exactly what would push them in that direction—and, just as important, what would prevent a wave of dip buyers from swarming in and canceling out the move. For those concerned about market risk, there's still a chance to buy into high-yielding certificates of deposit. Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s Marcus, for instance, offers the opportunity to save for as long as six years with an annual percentage yield of 2.95 percent.

Money-market fund managers, meanwhile, still have time to get ahead of what appears to be the start of a period of Fed interest-rate reductions. They're going to “want to have dry powder,” Mark Cabana, head of U.S. interest rate strategy at Bank of America, said at the symposium on Tuesday, referring to the ability to handle investor withdrawals.

The difficult question remains just how far the Fed will go in lowering interest rates. Chair Jerome Powell, in his press conference after the central bank's latest decision, noted that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” in this era of near-zero rates. (He used the same phrase in a panel discussion on Tuesday.) That could be taken to mean policymakers will act quickly and decisively, and then stop to see how that flows through to the economy and financial system. On the other hand, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, who dissented at the June meeting in favor of lowering rates, said on Bloomberg TV on Tuesday that the current situation doesn't call for a 50 basis point cut.

In that case, money-market rates would be lower but hardly decimated. As Alex Roever, head of U.S. rates strategy at JPMorgan Chase & Co., noted to Bloomberg News' Alex Harris, in 2007 and 2008, when the Fed swiftly took interest rates to near zero, “it wasn't the fact that they had to cut rates” that damaged the industry but that “the overall level of rates got so low.”

It has been a slow but steady comeback from the doldrums for money markets. Historically, according to Roever, the exodus tends to be the same, with outflows starting a year or two after the Fed begins to ease. At the same time, no prior period has had $13 trillion of negative-yielding debt worldwide. Just because there's already been a rush toward higher yields in the U.S. doesn't mean it can't go further when interest-rate cuts begin.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.