U.S. corporations brought back offshore profits in record numbers last year, with nearly half of the repatriated funds coming from low- or no-tax countries where companies had stashed cash prior to the 2017 tax law.

Nearly half of the cash U.S. multinationals brought back onshore during 2018 came from Bermuda (at $231 billion) and the Netherlands ($138.8 billion), according to figures released by the Commerce Department's Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) today. Ireland was the third largest source of repatriated cash, but the value is suppressed because of confidentiality rules in the country, according to the report.

The data give one of the first indications at how U.S. companies are deploying cash globally following an overhaul of the U.S. tax system, which cut the corporate tax rate to 21 percent, from 35 percent, and changed how the IRS taxes overseas corporate profits.

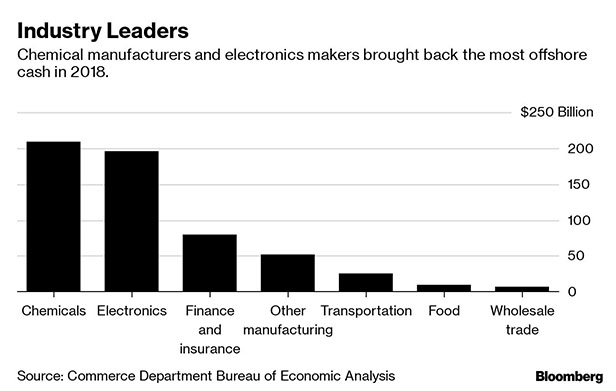

The figures show that chemical manufacturers and electronics producers—two industries that have historically relied heavily on offshore subsidiaries for tax purposes—brought back the most. The data also show that U.S. direct investment abroad decreased by $62.3 billion, to $5.95 trillion, in 2018 as a result of companies repatriating cash.

The data give lawmakers a sense of how much the law, which overhauled how global companies pay taxes, changed corporate behavior.

“Repatriation activity going forward will probably look different,” said Gordon Gray, director of fiscal policy at the American Action Forum. “You'll see net disinvestment from tax havens and more dividends” from where customers and manufacturing facilities are located.

U.S. corporations brought back about $876.8 billion over 2018 and the first quarter of 2019, according to Commerce Department figures released last month. That's a fraction of the $4 trillion that President Donald Trump said would be returned to the U.S. as a result of his tax law.

Tax Avoidance

Companies had kept much of their overseas profit offshore to avoid a 35 percent tax that kicked in when they brought the money back to the United States. The Republican tax law set a one-time tax rate of 15.5 percent on cash and 8 percent on non-cash or illiquid assets repatriated to the U.S., regardless of where the profits sat.

Going forward, companies generally only pay U.S. taxes on the profits they earn domestically. However, the law included some exceptions, which means companies can still owe on foreign profits. The global low-tax-intangible income levy, or GILTI, in the law was meant to keep U.S. corporations from stashing profits in low- or no-tax countries.

Economists and some tax lawyers have said GILTI actually encourages companies to earn money overseas, the opposite of Congress's intention. Policymakers in Congress and the Treasury Department are closely watching how companies react to the law, to see whether there are unintended holes that allow corporations to minimize their tax bills.

Many corporations asked the IRS for more time to file their tax returns for 2018, the first under the new tax law. Once those are filed, it can take years for auditors and companies to resolve disputes about how much tax they owe.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.