It may be a cliche, but it's true that the stock market isn't the economy. Values fluctuate based on a seemingly infinite number of variables, from the real (earnings) to the intangible (sentiment). So even though U.S. equities are near all-time highs, that isn't necessarily a sign that all is well with corporate America.

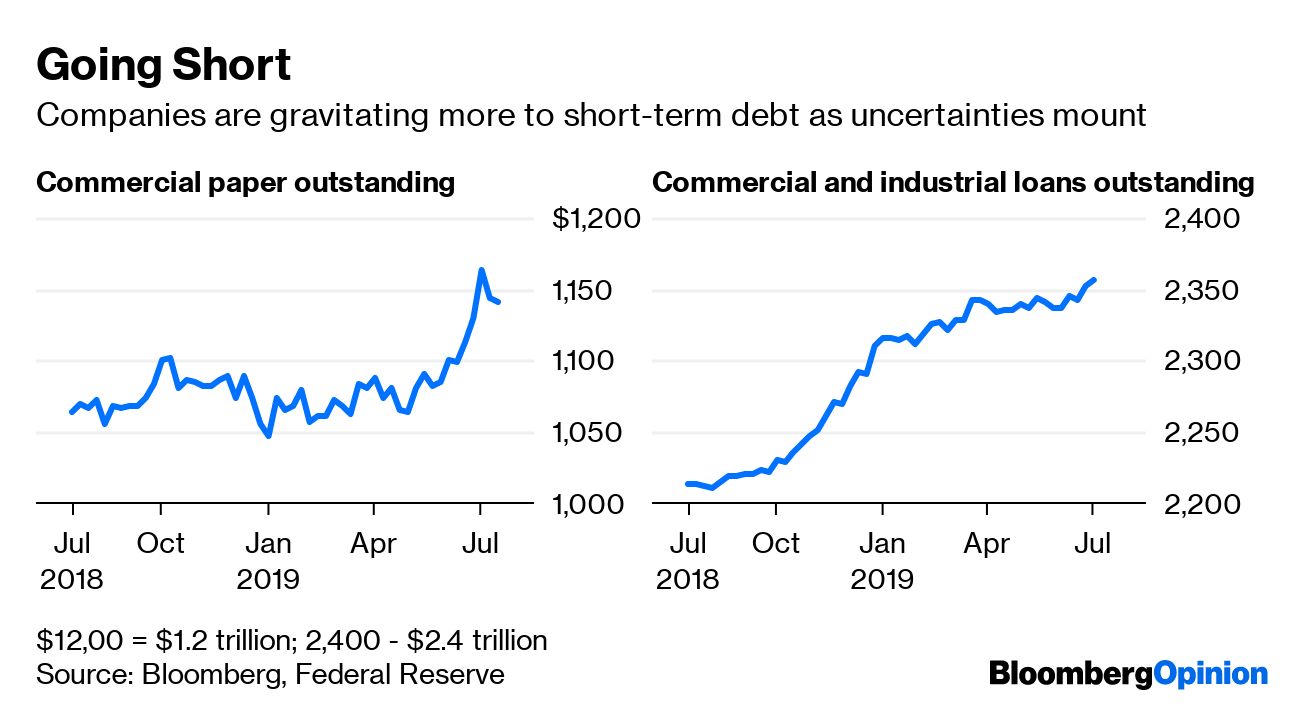

One sign that executives may not be all that confident in the outlook is the market for commercial paper. Even with a slight pullback the last two weeks, companies have been issuing these short-term corporate IOUs at pace not seen since 2011. The amount outstanding has jumped from $1.05 trillion at the start of the year to as much as $1.16 trillion earlier this month, according to the Federal Reserve. Although the amount eased back to $1.14 trillion in the latest weekly data that was released last week, that's still more than at any time in the past eight years.

Few markets are as opaque as the one for commercial paper, which typically matures anywhere from 15 days to nine months after it's issued, and it's never exactly clear why it expands or contracts. But it's hard not to interpret this latest jump as a down-arrow for the economy. It's a signal that companies may not have the confidence to commit to long-term loans or issue bonds, and instead want to wait out the uncertainty with shorter-term funding.

Fed data on commercial and industrial loans back up that idea, with growth grinding to a halt in the second quarter, increasing by just 0.15 percent, to $2.34 trillion. That's the smallest increase since the end of 2017. The slowdown came even as the Fed's most recent quarterly survey of senior loan officers showed that banks in aggregate eased some key terms for commercial and industrial loans to large and middle-market firms. So even though banks were willing to lend, companies had little appetite.

“Manufacturing, trade, and investment are weak all around the world,” Fed Chair Jerome Powell said earlier this month in his semi-annual testimony to Congress.

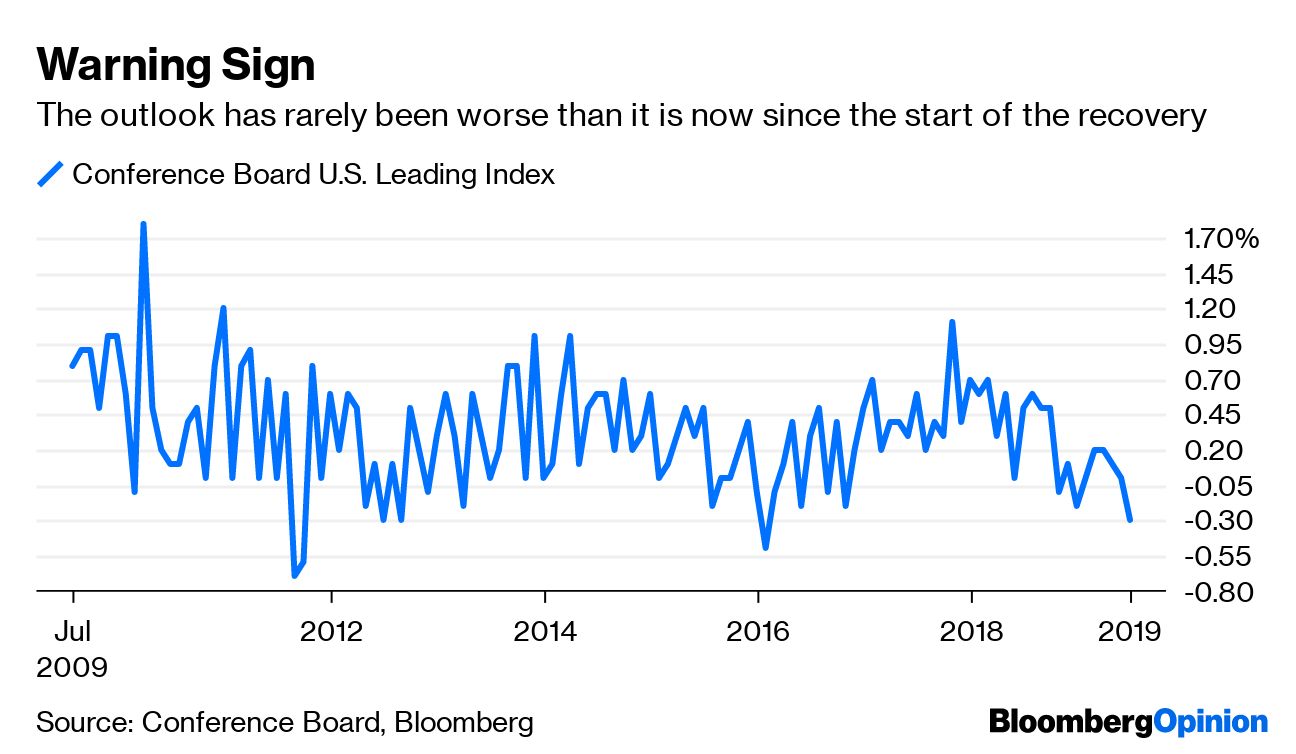

In addition, the Institute for Supply Management said on July 1 that its gauge of new orders for factories fell to 50, the lowest since December 2015 and equaling the dividing line between growth and contraction. Moreover, last Thursday, the Conference Board said its Leading Economic Index, which is intended to provide a sense of where the economy is headed, fell in June by the most since early 2016.

While it's still early, the signals being sent by companies that have reported results so far this earnings season aren't encouraging. Railroad operator CSX Corp. cut its revenue outlook for the year on Tuesday. Fastenal Co. and MSC Industrial Direct Co., which are often viewed as an economic proxy because they sell factory-floor and construction-site basics ranging from nuts and bolts to welding equipment, both noted a slowdown in demand in the most recent quarter.

You can't blame companies for being cautious. The U.S. is stuck in a trade war with China that seems to have no end, corporate earnings growth has stalled, and the political divide in Washington is as great as ever. These aren't things that can be fixed by a Fed interest-rate cut.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.