Concerns about cybersecurity are growing every day. Treasury and risk professionals need to watch for, and guard against, payments fraud, ransomware, and data breaches, while also ensuring security is adequate within third-party vendors of the applications and cloud services their company relies on.

Meanwhile, the pressure is on from regulators. The latest SEC guidance on the topic encourages public companies to disclose cybersecurity risks and to describe in financial terms any exposures that are material from a business perspective. To effectively meet this guidance, treasury and finance managers should answer some basic questions about their cybersecurity risk posture:

- What risks do we face?

- What is the financial value of these exposures?

- Which risks pose the largest threat?

- How much should we spend, and where, for best results to mitigate these risks?

Gathering this information is crucial to effective cyber risk management—but finance managers who embark on this journey will soon discover the Great Cybersecurity Exception. According to conventional wisdom in IT security circles, cyber risks cannot be assigned the same type of dollars-and-cents valuation as other risks because cyber risks are too technical and too dynamic, and historical data is too hard to find. Instead, cybersecurity professionals are often satisfied with designating cyber risks either red, yellow, or green on a heat map, based on their best guesses. Or they might show the progress they've made in reducing cyber risks by checking off tasks on a best-practices checklist like the NIST Cybersecurity Framework.

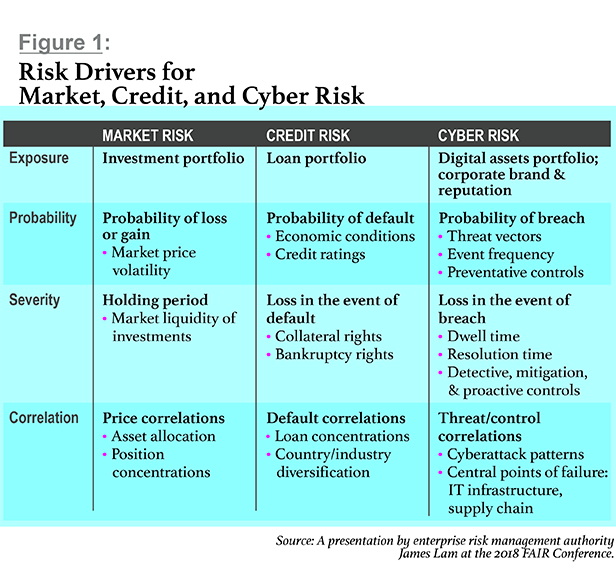

For years, cyber professionals have settled for these and similar approaches, but that's simply not good enough anymore. Cyber risk management is undergoing the same evolution that market risk, credit risk, and other forms of operational risk have undergone:

Market risk was once thought too hard to quantify, especially for derivatives and mortgages, where there is some optionality. Then we developed options adjusted spread (OAS) models that enable companies to quantify market risk.

Credit risk. General consensus once held that businesses' counterparty relationships were too complex for credit risk to be aggregated, but companies routinely do that today.

Operational risk. In the mid-1990s, it was thought that the individual company typically doesn't have enough losses or incident data specific to its business to effectively model its operational loss profile. Risk management professionals fought that issue and have largely overcome it.

Strategic risk. Major strategic decisions—an acquisition or development of a new product, for example—were once measured only in qualitative terms. Now, yardsticks adapted from financial risk—economic capital and risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC)—are routinely applied to strategic risks as well.

Through the years, finance professionals and consultants have repeatedly believed that a particular form of risk could not be quantified, or that companies can't collect enough data to accurately quantify risks—only to eventually be proven wrong. These are the same excuses you'll hear about cyber risks today. Sophisticated cybersecurity managers see that their discipline fits into a continuum with other risk disciplines, where new risk models and mathematical simulations enable risk management to evolve until they provide an effective means of measuring each new form of risk. (See Figure 1.)

Factor Analysis of Information Risk from the FAIR Institute has emerged as the international standard for quantification of cyber risks. In use at 30 percent of the Fortune 1000, the FAIR model enables sophisticated risk management teams to quantify cyber risk in financial terms. A FAIR analysis can enable IT analysts to make risk-based decisions about cybersecurity, and to communicate those risks in business terms to management and other corporate functions.

When paired with standard mathematical simulations, such as Monte Carlo, the FAIR approach becomes a cyber value-at-risk (VaR) model that mirrors the loss distribution approach (LDA) commonly used in the banking industry to meet capital requirements under Basel II. Similar to LDA, the FAIR model generates an annual loss distribution based on the projected frequency and magnitude of cyber events. The output of the model is an expression of cyber risk in financial terms.

As a result, organizations can:

- assess their risk from ransomware, payments fraud, and data breaches;

- estimate the probability of losses, even absent extensive data on that specific organization; and

- compare prospective security investments based on return on investment (ROI) projections.

Most significantly, companies can use the FAIR model to assess cyber risk in the same way they quantify their other enterprise risks. This means that cybersecurity risks can be incorporated into the broader enterprise risk management (ERM) effort, and investments in cyber protection can be compared directly against other potential investments, from both a security and a business opportunity point of view.

Digging into the FAIR Model

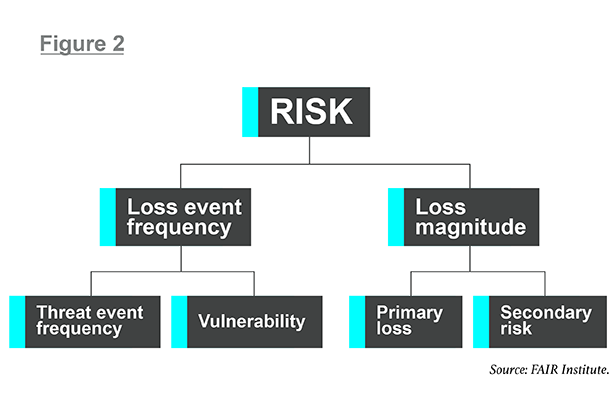

The FAIR methodology addresses two longstanding limitations in cyber risk analysis: lack of a consistent terminology to discuss risk and lack of a model for estimating losses in financial terms. At its most basic, a FAIR calculation looks like this:

Risk = Probable frequency x Probable magnitude of future loss

A tight definition of the risk scenario is key to a FAIR analysis. For example, a company might want to analyze the risk associated with cybercriminals breaching personally identifiable information (PII) from a specific "crown jewel" database. Key factors in this scenario would include:

- the asset (the PII);

- the threat (cybercriminals); and

- the potential effect (loss of confidential information).

Any FAIR analysis must involve a loss that can be quantified. While that may sound obvious, it hasn't always been the case in cybersecurity. Loosely defined "risks"—such as "the cloud" or "hackers"—have often sent analysts down a rabbit hole and perpetuated the notion in the industry that cyber risk simply can't be quantified.

Analysts need to be able to estimate the frequency at which a loss event (such as a data breach or ransomware attack) will occur in a year, as well as the magnitude of financial loss that any such event can be expected to cause. If they have this information, they can estimate how much risk results from the scenario.

When they have a workable scenario, with risks they are capable of quantifying, analysts can apply the model, as shown in Figure 2. The FAIR model breaks down frequency and magnitude into subcomponents. Analysts can estimate each element based on information collected from company subject matter experts or industry reports, then build back up into accurate overall estimates of risk.

To continue with our example, the company trying to calculate the risk to PII in its crown jewel database will need to estimate loss-event frequency—the number of times over the next year that cybercriminals are expected to successfully access the PII in question. Analysts can derive loss-event frequency using the two factors below it in the model: threat-event frequency (the number of times they expect, based on experience, that a criminal will attempt to breach the PII database) and vulnerability (the proportion of attempted breaches that are successful). Analysts can generate these values for loss-event frequency by running thousands of Monte Carlo simulations that show probabilistic outcomes for a range of results.

On the loss-magnitude side, the model guides the analyst to identify potential costs for the primary loss—which would include response costs, such as IT department efforts to counter the breach, help-desk staff to handle customer complaints, legal and communications team work—and additional, secondary losses, such as buying credit monitoring for customers, paying fines or lawsuits, or even revenue losses expected because customers demand a contract renegotiation.

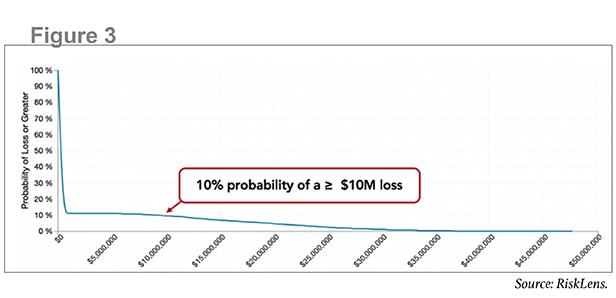

With the frequency and magnitude inputs, the FAIR model can generate a probabilistic statement of how much loss the organization is likely to experience, as illustrated by the loss exceedance curve in Figure 3. Purpose-built software can streamline these calculations. In this case, the model indicates that there is a 10 percent probability that this scenario—a hacker stealing PII from this specific database—will result in a loss to the organization of $10 million or more.

Where to Start with FAIR Analyses

A common starting point for organizations is to identify their top 5 or 10 risk scenarios, then run those risks through the FAIR model. Many organizations are surprised by the results. Seemingly dire, high-magnitude loss events may turn out to be so unlikely that they shouldn't be a top concern. On the other hand, loss events in which each occurrence incurs a fairly low cost may turn out to actually present high risk because they occur with high frequency.

If the FAIR software also includes sensitivity-analysis capabilities, analysts can tweak the inputs and see how they affect the loss results. What if the company reduces threat-event frequency or vulnerability by investing in better controls? What if it reduces potential secondary losses by reducing the number of records in the PII database?

Analysts can compare the costs of risk-reduction measures against the probable savings achieved by preventing losses resulting from cybersecurity failures. Such a cost-benefit analysis can help companies estimate the ROI of different cybersecurity spending options.

In addition to the obvious business benefits of more accurately estimating risks, FAIR analyses also help IT teams meet external demands that they communicate more clearly about cybersecurity. Corporate boards are now asking pointed questions about cyber exposures, in the wake of massive data breaches and ransomware attacks that have caused material losses to large organizations in recent years. As an example, the 2017 ransomware attack called NotPetya cost $870 million for Merck, $400 million for FedEx, and $300 million for Danish logistics giant Maersk.

The pressure is on from regulators as well. The 2018 SEC guidance on cybersecurity risk management directs public companies to disclose their significant risk factors in financial terms in their reports to the agency. The document reads like an output from a FAIR analysis. Disclosures should include:

- frequency of cyber events based on past experience;

- probability and magnitude of incidents (costs, in financial terms);

- adequacy of controls; and

- fines and judgments that might result from a cybersecurity incident.

The guidance document calls for public companies to "provide for open communications between technical experts and disclosure advisors." Once, not long ago, that was a nearly impossible ask. No longer. Now, translating cyber risks into business and finance terms is a realistic endeavor, thanks to the revolution currently occurring in cyber risk measurement.

Nick Sanna is the CEO of RiskLens, with responsibility for the definition and execution of the company's strategy. In 2015, Sanna championed the creation of a nonprofit organization, the FAIR Institute, focused on helping organizations manage cyber risk from the business perspective. He currently serves as president of the FAIR Institute, through which he helps risk officers and CISOs get a seat at the business table.

Nick Sanna is the CEO of RiskLens, with responsibility for the definition and execution of the company's strategy. In 2015, Sanna championed the creation of a nonprofit organization, the FAIR Institute, focused on helping organizations manage cyber risk from the business perspective. He currently serves as president of the FAIR Institute, through which he helps risk officers and CISOs get a seat at the business table.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.