By all accounts, it was supposed to be a sleepy August for the U.S. corporate bond market.

Three weeks ago, the thinking went something like this: Sure, the Federal Reserve would cut its benchmark lending rate on July 31, in what Chair Jerome Powell would call a "mid-cycle adjustment." But Treasuries were already pricing in such a move on the short end. Further out on the curve, the 30-year yield was about 2.6 percent, still more than 50 basis points (bps) away from its all-time low. Ten-year yields were about 2 percent, which seemed like a comfortable range for both buyers and sellers. For company finance officers, it had the makings of a sellers' market but one that would be around once summer drew to a close.

Then things got crazy. The 30-year yield lurched lower by 8 bps on August 1, then 13 bps on August 5, then another 13 bps on August 12. After a one-day reprieve near its all-time low of 2.0882 percent, it cruised through that level, tumbling to as low as 1.914 percent. The rally was so intense that the U.S. Treasury Department made an unusual, unscheduled announcement that it was again exploring issuing 50- or 100-year bonds.

Companies clearly felt they couldn't afford to pass up this opportunity. In the first full week of August, CVS Health Corp., Humana Inc., and Welltower Inc. headlined $35 billion of debt sales among investment-grade firms, easily surpassing estimates. Then in the week of August 16, more than $22 billion went through, including a rarely seen offering from Exxon Mobil to the tune of $7 billion. Market watchers expected that would just about wrap things up until after Labor Day on Sept. 2.

Some finance officers had other ideas. 3M Co. borrowed $3.25 billion on Monday to help finance its acquisition of medical-products maker Acelity Inc. In total, issuers sold $6.65 billion of investment-grade debt on August 19, already topping some predictions for $5 billion this week. Then on Tuesday, Bank of New York Mellon Corp. priced $1 billion at the lower end of its expected yield range, along with a handful of other borrowers with multimillion-dollar deals.

All this is to say, companies are simple: They see staggeringly low yields, and they issue bonds.

Investors, for their part, can't get enough of them. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index has returned 13.3 percent so far in 2019. Over the past 12 months, the index is up 12.5 percent, compared with just 1.5 percent for the S&P 500 Index. The average spread on corporate bonds has widened to 122 bps, from 107 bps at the end of July, but that's just because they couldn't keep up with the relentless rally in Treasuries, not because of a lack of buyers.

If Bank of America Corp. strategists led by Hans Mikkelsen are correct, the demand in credit markets has lasting power. They say the $16 trillion of negative-yielding debt globally has left investors—and particularly those outside the United States—with few alternatives besides purchasing companies' debt. "There is a wall of new money being forced into the global corporate bond market," they wrote on August 16. "Given the near extinction of non-USD IG yield, foreign investors are forced to take more risk."

Of course, buying investment-grade bonds hardly qualifies as a speculative endeavor. Exxon Mobil, in fact, has the same credit rating as the U.S. government from both Moody's Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings. On the other hand, Bloomberg News's Jeannine Amodeo and Davide Scigliuzzo reported this week that three leveraged-loan sales which had been languishing in the U.S. market for weeks were pulled as investors sought higher-quality assets. Vewd Software became the fourth on Tuesday, scrapping a $125 million term loan due to market conditions. Leveraged loans, it should be noted, are floating-rate securities and so face weaker demand when the Fed appears poised to cut rates, as it does now.

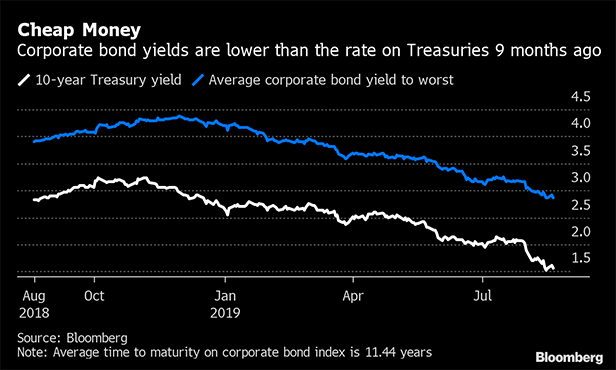

But the behavior of large, highly rated companies in recent weeks is exactly what should be expected. Exxon Mobil issued 30-year bonds to yield 3.095 percent. In November, five-year Treasuries offered the same amount. 3M, rated a few steps below triple-A, priced 30-year debt to yield 3.37 percent, less than the going rate on long Treasury bonds just nine months ago. No matter how you slice it, they're getting borrowing costs that seemed unthinkable around this time last year.

Interestingly, these low yields should be encouraging governments to borrow more, too. I wrote last week that the bond markets were begging for infrastructure spending. However, it seems neither Germany nor the U.S. has any appetite for that sort of initiative. The German government is reportedly preparing fiscal stimulus that could be triggered by a deep recession, while President Donald Trump hasn't ruled out a payroll tax cut to stave off any economic weakness.

It's certainly possible that U.S. yields will only fall further from here, and other companies can also borrow or refinance at rock-bottom interest rates. But the move in global bond markets in recent weeks was extreme, to say the least. The weak demand for Germany's 30-year bond auction on Wednesday, which offered a coupon of 0 percent at a yield of -0.11 percent, suggests there are at least some lines that investors won't cross.

For prudent companies, it was well worth delaying summer vacations to get their deals done.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.