Maybe the third time Jerome Powell will get lucky.

The Federal Reserve chairman looked close to pulling off a soft landing of the ebbing U.S. economy twice this year—at the start of May and the end of July.

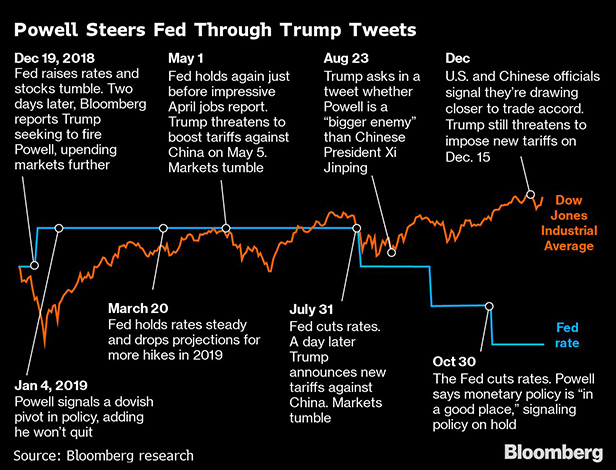

Each time, though, he saw his plans blown off course via an escalation of trade tensions by President Donald Trump. Things were bad enough in August that Powell delayed his vacation by a day to assess the fallout.

As he approaches his third year as Fed chairman, Powell is again sounding confident that the U.S. economy and monetary policy are in a good place, calibrated to help extend the record-long U.S. economic expansion.

Reflecting his contentment, Powell and his colleagues are expected to leave interest rates unchanged on Wednesday after cutting them at three consecutive meetings. And they're keeping their fingers crossed that Trump will decide not to follow through on his threat to impose more tariffs on Chinese imports on December 15.

See also:

- Assessing the Impact of the Fed's Interest Rate End Game

- Interest Rate Response for Small and Midsize Companies

- Incorporating Expectations into Hedging Decisions

"The jury is still out, but it's very much looking like a soft landing," said Princeton University professor Alan Blinder, who served as Fed vice chairman from 1994 to 1996, the last—and arguably only—time the central bank cooled off the economy without crashing it into recession.

A recession probability model developed by Bloomberg economists puts the odds of a contraction in the next 12 months at about one-in-four, down from close to one-in-two a year ago when financial markets were spooked by what even some Fed insiders admit was a poorly executed December rate increase.

"One can argue that at the end of 2018 they were a little slow to recognize that things had turned," former Fed Vice Chairman Donald Kohn said. But Powell "corrected it within weeks" by signaling that the Fed was putting further hikes on hold.

How things go from here is critical not only for Powell's legacy, but also for the reputation of the politically independent central bank as it faces an onslaught of criticism from the president.

The Trump-Powell Dynamic

Trump has a lot riding on Powell's ability to keep the economy purring. A 2020 downturn would probably imperil his chances of winning re-election in November.

At the heart of the interplay between Trump and Powell is a paradox. Fed insiders insist that Powell has turned a deaf ear to Trump's demands that he gin up growth by slashing rates. But after increasing rates four times in 2018, the central bank reversed course this year, acting quickly to shelter the economy from Trump's trade squalls and slow global growth.

"They've inadvertently encouraged the trade war" by anesthetizing the markets with preemptive rate cuts, said Ethan Harris, head of global economic research for Bank of America Corp.

The reductions have also raised questions about the Fed's susceptibility to political pressure.

"I worry that the committee will be thought of as less independent and less credible because they eased rates this year after the president criticized the Fed," said Yale University professor William English, a former senior economist at the central bank who nevertheless supported the rate cuts.

Going into 2020, Powell has suggested that enough is enough. He's said it would take a "material reassessment" of the Fed's outlook for moderate growth, a strong labor market, and inflation around 2 percent for it to move again.

Trump isn't satisfied with that stance, telling Powell in a rare sit-down on Nov. 18 that the central bank should push rates below zero.

He also argued that the Fed's monetary policy was hurting U.S. manufacturing exporters by elevating the dollar—even though the greenback is little changed from when Trump was elected and U.S. companies have expressed more concern about trade strains than interest rates.

Trump's assault on the Fed is not limited to angry tweets. Earlier this year, he asked White House lawyers to explore his options for removing the central bank chair. He's also floated the possibility of nominating economists sympathetic to his views to two open positions on the Fed board.

To protect the Fed's flank, Powell has continued to frequent the halls of Congress. Since taking over as Fed chair in February 2018, he's met or spoken by telephone with lawmakers more than 170 times outside of his appearances before Congressional committees.

Fed Gets an A-Plus… for Now

As part of a wide-ranging strategic review, the Powell Fed has also reached out to a cross-section of Americans—from small-business owners to food bank managers—to get their feedback on how the central bank is doing.

"I would give him an A-plus" on handling the political dimension of the job, said Kohn, who is now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. "He's built a moat around the Fed through his communication with Congress and the public."

Indeed, when Powell appeared at a chamber of commerce meeting in Providence, Rhode Island, last month, more than 700 local business leaders gave him a prolonged standing ovation as he took the stage. His message to them was upbeat: "At this point in the long expansion, I see the glass as much more than half full."

By allowing unemployment to fall to around half-century lows, Powell is helping to spread the benefits of the economic upswing to those less well-off, in the process bolstering the Fed's reputation on Capitol Hill.

The question now for Powell—and Trump—is whether the Fed chief can keep the economy on a roll.

Allianz SE chief economic adviser Mohamed El-Erian worries the Fed has become too beholden to financial markets and wasted precious monetary ammunition by lowering rates in October.

"It wouldn't surprise me if the markets start pressuring the Fed to cut again" as it becomes clear that trade tensions aren't going away even if Trump reaches a mini-deal with China, said El-Erian, who is also a Bloomberg Opinion columnist.

But the way Fed insiders see it, they didn't cut rates in 2019 merely to keep markets happy any more than they bowed to Trump's constant hectoring. Instead, they were seeking to protect the economy from the fallout from Trump's tariff battles.

The dynamic in 2020 may be much the same. The economy's fate, central bankers believe, hinges largely on whether Trump can make progress on trade—or at least avoid making things more fraught. That, in turn, will determine what they do with interest rates.

"The outlook is very much held hostage to the degree of uncertainty coming from trade policy," said Julia Coronado, the founder of MacroPolicy Perspectives in New York and a former Fed board economist.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.