The Federal Reserve is running the risk of fomenting an eventual financial crisis by easing banking regulations at the same time that it's cut interest rates.

So say some former Fed officials, including ex-Vice Chairman Alan Blinder and financial stability experts Daniel Tarullo and Nellie Liang. They worry that the combination of looser credit and laxer rules will prompt financial institutions and investors to pile on leverage and take excessive risks. While that may spur economic growth in the short run, it could end up triggering a recession once the speculative bets are unwound.

"When you lower rates and put incentives in place to increase borrowing, it should not be surprising that risks will increase," said Liang, former director of the Fed's financial stability division. "That means this is not the right time to be also significantly loosening financial regulations."

U.S. stocks have risen to record levels and junk-bond yields have sunk to five-year lows this week on hopes that a partial U.S.-China trade deal will boost global growth already buttressed by easier credit. After lowering rates three times, Fed policymakers left them unchanged on December 11 and forecast they would stay that way through the 2020 presidential election year. The central bank has also made or proposed various changes in financial oversight, including alterations to the stress tests that banks undergo and an overhaul of the Volcker Rule's trading restrictions.

Republican lawmakers and banks have complained that the Fed has not gone far enough in easing rules, while Democrats such as presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren have warned the central bank against loosening its regulatory grip.

Liang, who was nominated by President Donald Trump to the Fed board but withdrew her name after opposition from some lawmakers, voiced concern about mushrooming corporate credit. "I worry that defaults and investor losses will be higher than expected in the next downturn and will make the next recession more severe," she said.

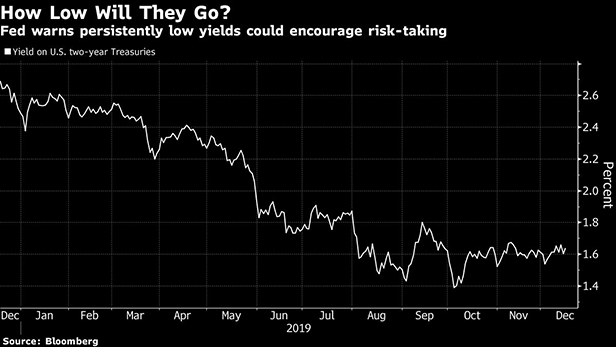

In its latest financial stability report, the Fed's board said a prolonged period of low rates could undermine financial stability by prompting profit-pinched banks and other firms to take more risks. However, Fed leadership though has pushed back hard against suggestions it has made the financial system more vulnerable by loosening regulations, arguing that the capital requirements of the biggest banks remain as tough as ever.

The U.S. has "a stable, healthy, and resilient banking sector," Randal Quarles, Fed vice chairman for supervision, told lawmakers on December 4. He said that the Fed's focus has been on tailoring the regulation of regional and smaller lenders. "One of our principles has been to ensure that we do not reduce, in any material way, the loss-absorbing cushion of the institutions," he said "I think we have succeeded in doing that."

Former Fed Governor Tarullo is not so sure. He zeroed in on the stress tests, including the disclosure of more information about the models behind them. "I suspect quite strongly that the effective amount of capital the banks have to have for a given portfolio is lower because they have so much more information about the stress tests," said Tarullo, who was the Fed's point man on regulation after the 2008 crisis and is now at the Harvard Law School.

Ex-central bank Vice Chairman Donald Kohn welcomed efforts to tailor rules to fit the size of the institution but cautioned regulators against taking their eye off of "very sizable" regional banks. "You get a bunch of regional banks all doing the same thing at the same time, then that could be systemic," said Kohn, a member of the Bank of England's Financial Policy Committee. There's also "reason to be cautious about what's going on outside the banking system when you lower rates because you have fewer macro-prudential tools to deal with that sector," he said.

Changing Incentives Through Policy

Under the Dodd-Frank Act, the sweeping post-crisis regulatory reforms introduced to strengthen the banks, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) monitors the overall financial system. Headed by Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, it has the power to designate non-bank financial institutions such as insurance companies as "systemically important," and so subject them to increased regulation.

The council, which includes the heads of the Fed, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and other regulatory agencies, has recently shifted its focus toward monitoring potentially risky financial activities and raised its hurdle for singling out individual firms for more supervision.

"They come very close to saying that they're never going to designate a non-bank, no matter what," Tarullo said. "That almost defies the will of Congress." He also voiced doubts that the council has the authority or the desire to impose more regulation on financial activities.

Blinder said Trump appointees at other regulatory agencies were more to blame for what he called "backsliding." The Fed though is not immune and shouldn't be easing credit and bank rules simultaneously. "You can try to push up aggregate demand and expand the economy with lower interest rates, but don't drop your regulatory safeguards" as well, the Princeton University professor said.

Some current Fed policymakers share the concerns of their former colleagues. Fed Governor Lael Brainard has voted against some of the board's rule changes, while Boston Fed President Eric Rosenberg has called for higher bank capital in today's low interest rate environment.

Liang, who is friend of Powell's, said she agrees with him that financial stability risks aren't elevated currently. "If you took a snapshot of the situation now, it looks OK," the Brookings Institution fellow said. "But I worry about what the situation would look like in a year or two given the incentives from recent policy changes."

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.