At the height of last summer, New York Federal Reserve President John Williams temporarily roiled markets when he argued that central banks running low interest rates should act boldly to inoculate their economies against unfolding ailments.

"When you only have so much stimulus at your disposal, it pays to act quickly to lower rates at the first sign of economic distress," he said in a speech that the New York Fed later clarified was not meant to be a policy signal. You want to "vaccinate against further ills."

As Williams and his colleagues prepare for a monetary policy meeting next week, the mounting economic impact of the coronavirus is turning his academic theorizing into a practical consideration for policy: Should the Fed cut interest rates to zero? And, if so, how soon should it act?

The argument for such a move, sooner rather than later is based on research like that of Williams, which contends that central banks should not conserve their ammunition when rates are near zero and economic threats arise.

The argument for a more cautious approach rests on the huge uncertainties surrounding the spread of the virus and its effects on the economy, as well as the scope of any measures from the Trump administration.

Decision Complicated by Lack of Data

"They have literally no data as to the economic impact of the coronavirus," said Justin Weidner, an economist at Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. The bank currently forecasts 50 basis points (bps) of cutting this month, with the possibility of more as Fed officials see additional data.

"It is hard to say 'Use all of your ammunition' when you don't know what you are shooting at or what the scope of the fiscal response is," he said.

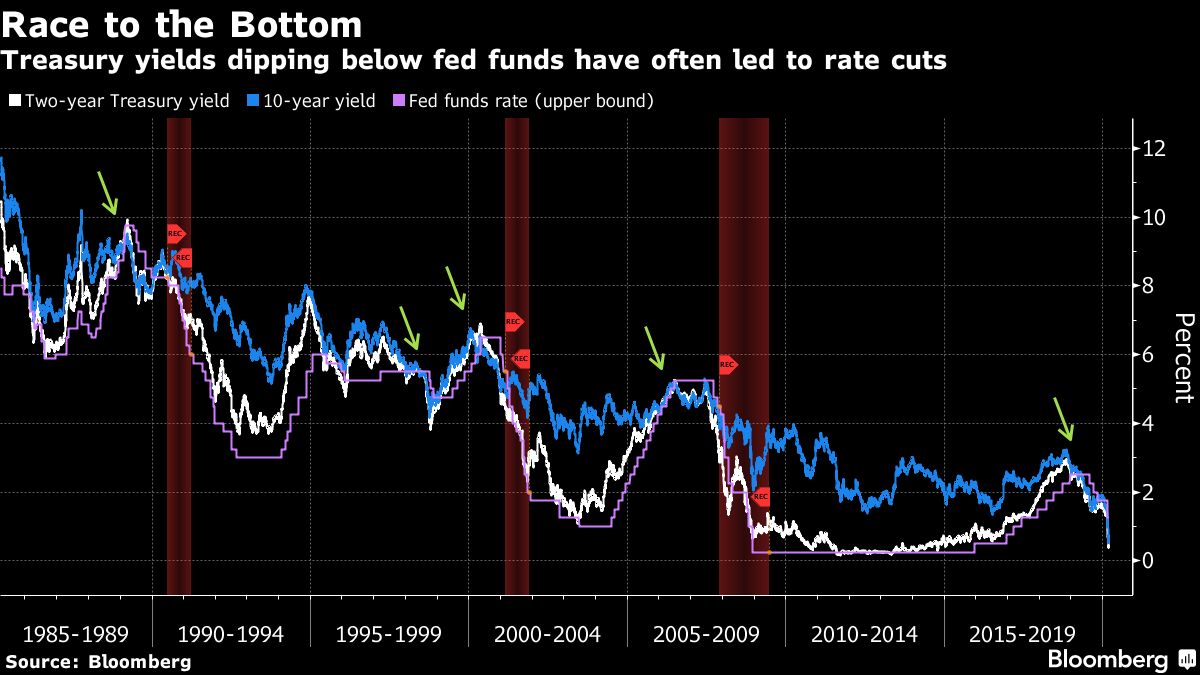

After an emergency half-percentage-point reduction last week, the Fed's target range for the overnight interbank rate stands at just 1 percent to 1.25 percent.

Traders in the federal funds futures market are betting that the central bank will lower rates by at least another half point at its March 17-18 meeting.

A number of Fed watchers—Michael Feroli of JPMorgan Chase & Co., Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs Group Inc., and former U.S. central bank governor Laurence Meyer, to name a few—predict that rates are headed to zero.

Feroli, who sees that happening at the Fed's next meeting if not before, invokes research like Williams' as justification for his call. "The reason for a maximally aggressive move at the next meeting has its roots in the optimal control literature, which recommends moving quickly when the effective lower bound on interest rates looms," JPMorgan's chief U.S. economist said in a March 9 note to clients.

In his July 2019 speech, Williams said his work shows that the Fed can magnify the impact of its limited interest rate ammunition by acting quickly. It can also enhance its monetary policy firepower by keeping rates lower for longer once they've been cut.

Hatzius sees the Fed getting to zero in two steps, with a half-point cut both this month and next. The Goldman Sachs chief economist expects that to be accompanied by action by other monetary authorities, including the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, as policymakers battle a contraction in the world economy.

In laying out the rationale for the Fed's March 3 emergency rate cut, Chairman Jerome Powell said it was partly designed to avoid a tightening of financial conditions that could hurt the economy.

Unfortunately for Powell and the Fed, financial conditions have gotten tauter since then, as the stock market has cratered. Behind the plunge: more bad news on the virus and the lack of action by other policymakers to aid the economy.

After days of playing down coronavirus risks, President Donald Trump's administration is moving toward a package of support, including a possible payroll tax cut. But that hasn't stopped the president from beating on the Fed and pressing it to cut rates more.

An Unconventional Economic Crisis

Amherst Pierpont chief economist Stephen Stanley said the monetary policy playbook put forward by Williams and others is meant to deal with a conventional recession that can be combated through easier monetary policy. The shock from the virus is different.

"This isn't an interest rate problem," he said. "People are going to stay home because they're afraid of getting sick" no matter how low rates are.

Stanley, who expects the Fed to reduce rates by a half-point next week, also sees downsides to the central bank moving too aggressively: It risks fueling the feeling among investors that it is running out of ammo. "The closer they move to zero, the more intense that feeling becomes," he said.

—With assistance from Sophie Caronello.

Recommended For You

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.