Corporate treasurers in crisis-fighting mode look set to miss looming deadlines to abandon the scandal-plagued LIBOR benchmark, threatening a showdown with regulators powering ahead with reforms.

In the grip of this once-in-a-generation pandemic, many businesses have already given up on this year when it comes to shifting away from the reference rate that has underpinned trillions of dollars in loans, bonds, and derivatives, according to the Association of Corporate Treasurers.

Lenders and borrowers risk entering a legal no man's land when the London interbank offered rate (LIBOR) expires at the end of 2021—relying on the generosity of regulators and counterparties for their contracts to be recognized.

The risks associated with LIBOR-linked loans are rising. In the U.K. from October, banks still using securities tied to the rate will be effectively penalized through a limit on their borrowing from the Bank of England (BOE), tightening their balance sheets and making it harder to lend to companies fighting for their lives.

U.K. officials said last month that firms should stick to the final target but acknowledged that the virus outbreak has affected the transition plans of many businesses.

Corporate treasurers "may be in their pajamas, but are working flat-out," said Caroline Stockmann, chief executive of the Association of Corporate Treasurers, a global trade body. "It's all about liquidity, all about survival, and not about the reference rate in over a year's time from now."

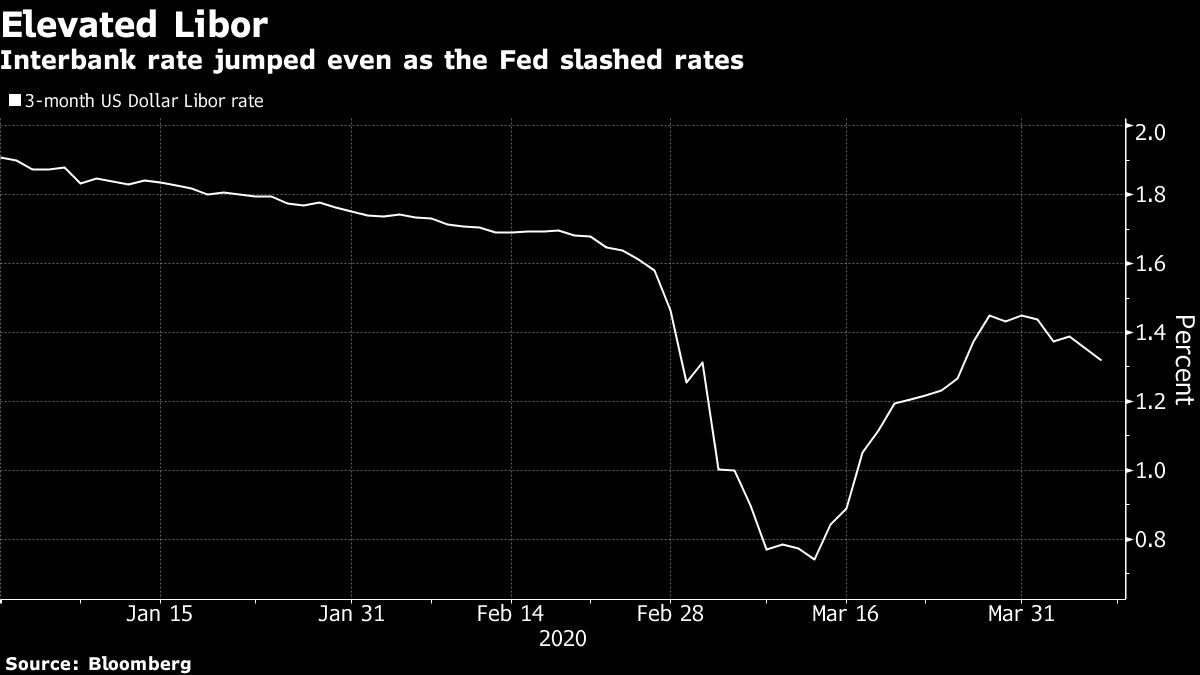

LIBOR was tainted after European and U.S. banks were found to have manipulated rates to benefit their own portfolios. The U.S. group that's guiding the transition to the new Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR)—the heir presumptive to LIBOR in dollar markets—revealed a framework last week for moving cash products from the old to the new benchmark.

Lawyers and consultants are warning corporations from Europe to America that missing the final deadline could materially impact repayment costs and liquidity, while the market volatility only underscores the benchmark's manifest flaws.

Smaller British companies with LIBOR-linked loans, in particular, could lag in their financial planning even as bankers forge ahead with their transition plans, said Ed Moorby, risk advisory partner at Deloitte.

Similarly, hedge funds, asset managers, and commercial borrowers and issuers of debt "were just coming to grips with the shift, and now this happens," said Michele Navazio, a partner at Seward & Kissel LLP in New York. "What are they doing now? The short answer is they are not worrying about LIBOR."

As Clock Ticks, Companies Add Fallback Language to Contracts

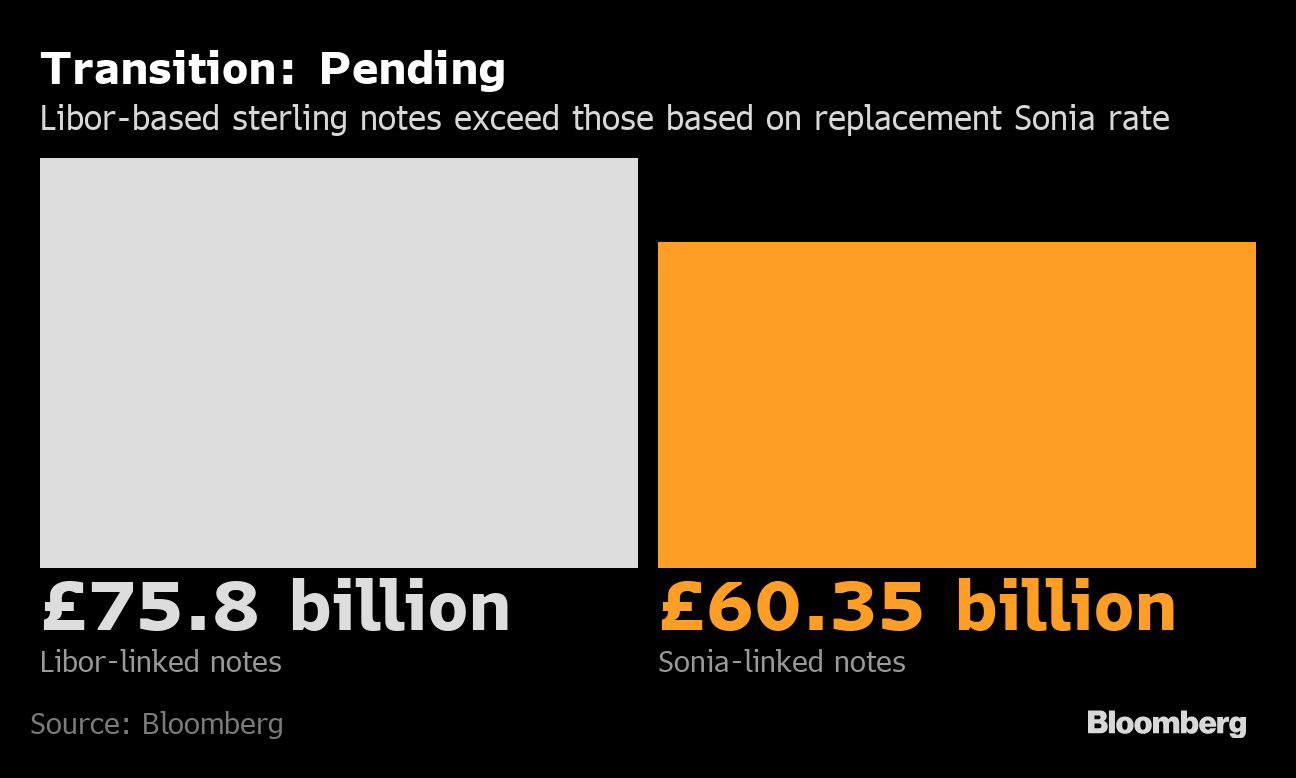

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the BOE said last month that the U.K. loan market has made less progress, which may affect some of the milestones.

The two agencies and the Working Group on Sterling Risk-Free Reference Rates "will continue to monitor and assess the impact on transition deadlines, and will update the market as soon as possible," they said at the time.

For now, banks have until the end of September to cease issuing cash products linked to sterling-denominated LIBOR. The FCA told asset managers to consider ceasing to launch new products with benchmarks or performance fees linked to the benchmark by then.

The demand to stop lending in LIBOR is the key concern, said Joshua Roberts, associate director at advisory firm Chatham Financial, who said the deadline was always very aggressive. "It's hard to imagine regulators forcing companies that are already struggling to access liquidity to stop borrowing on LIBOR if they're not set up for the alternative," he said.

In the U.S., the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC)—a body convened by the Federal Reserve that is helping to guide the transition—has effectively reminded firms that work on SOFR is still progressing and the deadline is still the end of 2021.

"The date hasn't changed," said David Bowman, special adviser to the Board of Governors at the Fed. "People can speculate. Maybe the date will change in the future."

Bowman said during a webinar hosted by consulting firm Oliver Wyman on Tuesday that some of the ARRC's near-term goals "will be delayed a bit" but encouraged participants to "find the places where you can continue your work."

Recent deals seen as helping the bond market's transition include the European Investment Bank's first dollar transaction tied to a compounded SOFR index and a sterling offering by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development that opens the path to a universal SONIA index.

As the clock ticks, companies are being advised to ensure they include fallback language in their contracts that allows the use of a replacement benchmark by the end of next year. This won't substitute for proper management of the transition, but it could help keep companies away from messy lawsuits. Without the fallbacks, "a customer who has a LIBOR-linked loan from you could say the contract is frustrated and you end up in litigation," Deloitte's Moorby warned.

Not everyone has abandoned their plans. Chatham Financial's Roberts said a number of funds are working intensively to find exposures and sort out legacy contracts. Many companies are hoping for an official delay, as happened with the MiFID II securities rulebook in Europe and the Dodd-Frank Act in the United States.

Yet this could lead to a regulatory game of chicken, with officials wary of easing the pressure in case LIBOR never ends.

"What used to be good isn't really working, and what's supposed to be replacing it isn't really working," said John Coleman, senior vice president at RJ O'Brien & Associates LLC in Chicago. "The fuse is burning."

—With assistance from Silla Brush, Lucy Meakin & Alexandra Harris.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.