When it comes to predicting or limiting the near-term wreckage that Covid-19 will visit upon the U.S., economists and policymakers can do little to help.

What happens after the virus passes is a different story. The strength or weakness of the country's rebound, whenever that comes, will be heavily influenced by actions taken today and over the coming months.

Economists pointed to three crucial areas they say will matter most. First, the speed with which small and midsize business aid finds its mark. Second, the level of support for states and cities later this year. And third, something—anything—to restore public confidence in getting back to life, and business, as usual.

A clean, so-called V-shaped recovery may be unrealistic, but effective steps on each of these fronts could help make the difference between an energetic bounceback and a recession that is long-lasting or even catastrophic.

"Where we are headed in the long run can be shaped, with unusual effectiveness, by policy decisions that are happening right now," said Kartik Athreya, director of research at the Richmond Fed.

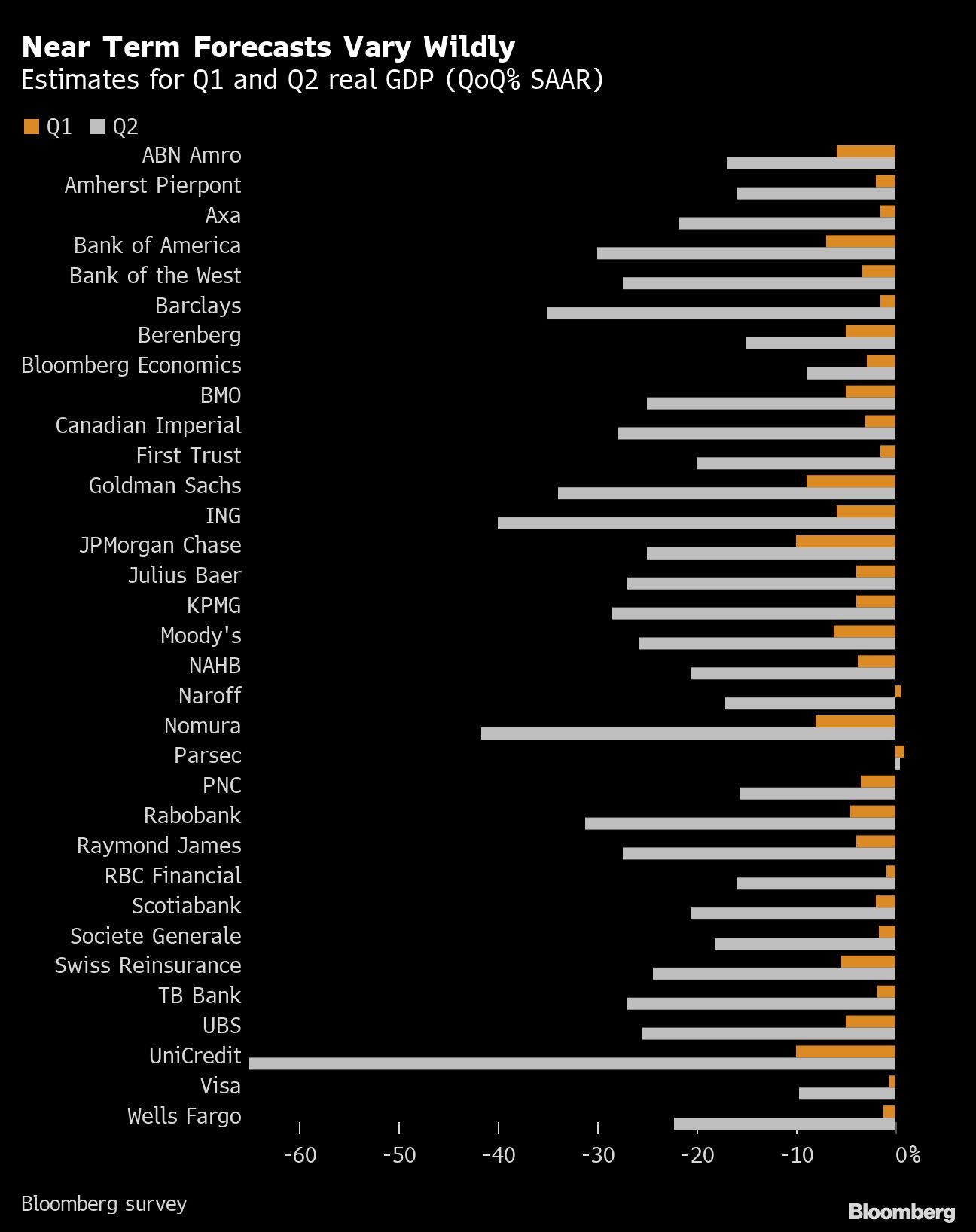

The unprecedented nature of the current contraction makes it almost impossible for forecasters to tell us how bad it's going to get. Their models, after all, rely heavily on documented historical experience. No surprise that forecasts span an eye-popping range: Estimates for second-quarter annualized GDP growth submitted to Bloomberg since April 10 range from a contraction of 65 percent to 0.4 percent growth.

Economists are even more powerless when it comes to issuing any prescription for improving the short-term outlook. With public health the priority, policy is focused on temporarily smothering activity that drives whole sectors of commerce.

To its credit, the federal government has made significant stimulus available. Congress in late March appropriated more than $2 trillion to beef up unemployment benefits, send direct aid to lower and middle-income households, offer grants to small businesses, and provide bailouts for airlines and other big firms. President Donald Trump swiftly signed the legislation into law.

Lawmakers are currently discussing even more funding for small businesses. The Federal Reserve has also announced a barrage of new emergency lending programs capable of mobilizing trillions more.

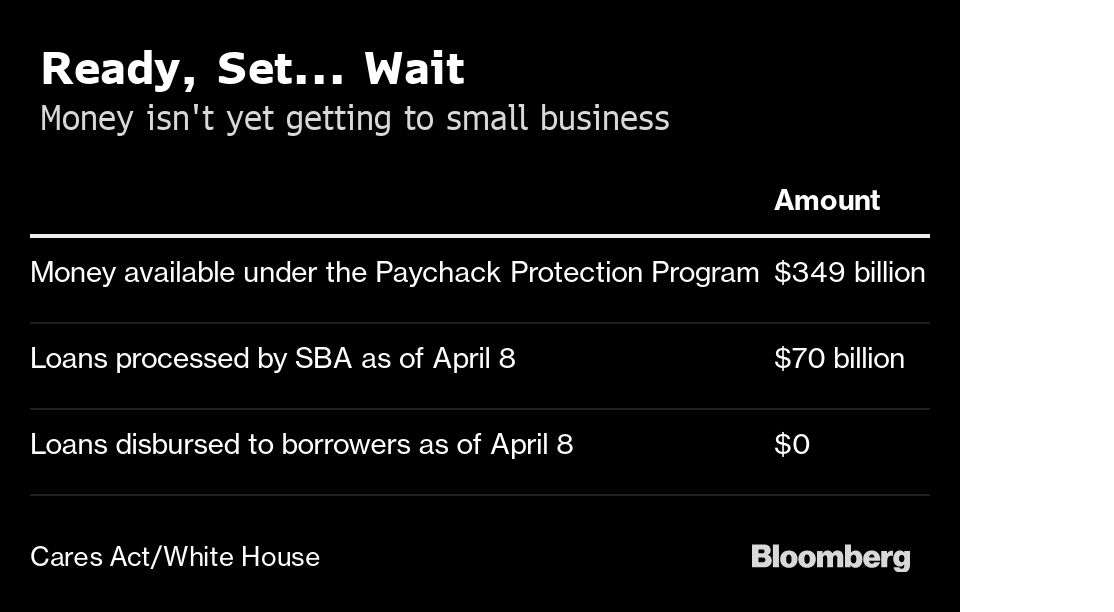

But what's desperately needed now is the rapid disbursement of cash. And so far, more than three weeks after the first stay-at-home orders were issued, very little money has been delivered.

The Paycheck Protection Program—created to hand out $349 billion to small companies through loans that convert to grants if a company retains or rehires its workers—got off to a rocky start. The White House said April 9 that $128 billion of loans had been processed. But very little, if any, of that money had actually been disbursed.

The Federal Reserve is preparing a separate program, the Main Street lending facility, that will make $600 billion in loans available to small and midsize companies. But even as officials revealed details of the scheme on April 9, they couldn't give any timetable for when it might open.

Fed vice chairman Randal Quarles said Friday that getting the loans to midsize U.S. businesses through the Main Street lending program is two to three weeks away.

"There's going to have to be a certain tolerance of imperfection" in getting aid programs running, said David Wilcox, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. "They cannot afford to be cavalier or haphazard, but they do need to recognize the urgency of the situation because economic dreams are being shattered on an daily basis."

Shizu Okusa and her employees at the Washington D.C.-based bottled juice company Jrink could be an example. Okusa has closed her brick-and-mortar outlets and laid off 30 of her 38 staff members as revenue collapsed by 80 percent.

On April 3 she applied for a $170,000 PPP loan that would enable her to rehire her staff and pay rent and other bills. Her bank, EagleBank, said they might be able to approve the application and release funds this week. But maybe not. Okusa is already exploring options, including the possibility of a merger or sale.

"It's like you're about to board a plane, and you're all hovering around the entrance waiting to board, but they're not letting you in," Okusa said.

Every business failure represents a miniature blow that rolls forward. Suppliers and vendors lose future revenue, and laid-off workers cut back on spending, further reducing demand across the economy. That can create what Columbia University's Glenn Hubbard, a former chief economist to President George W. Bush, has called a "demand doom loop." Without large and rapid government intervention, it could trigger a Depression-like downturn, he said.

Cities and States

Past the fire-wagon stage, Congress will have another chance to heavily influence the pace of the eventual recovery by bailing out cities and states, which are headed for major budget shortfalls as tax revenues plummet and coronavirus-related spending rises. Without help, they could be forced to make draconian cuts to spending and jobs.

That's what happened after the recession of 2007–09, contributing to the tepid recovery.

"The state- and local-government component is going to be critical because so many states have balanced-budget amendments," said Seth Carpenter, chief U.S. economist at UBS Securities LLC and a former Treasury official. "Any way to prevent contractionary fiscal policy, whether federal or state or local, is going to help differentiate the recovery after this recession from the last one."

Mitigating Long-Term Effects

The third challenge may be harder to address. Even if the novel coronavirus doesn't flare up again in the autumn or next year, the fear of its re-emergence may cause dramatic and long-lasting changes to social behavior—and, by extension, to economic activity.

The Great Depression cast a shadow on the saving and spending habits of millions of Americans for decades afterward. Even the Great Recession of 2008–09 had a documented impact. The current crisis could go deeper.

"This is not just a threat to your economic livelihood; it's a threat to your health," said Peterson's Wilcox. "It's going to affect behavior in more dimensions than I can begin to imagine."

With that in mind, steps that rebuild public confidence in normal activities will be central to restoring economic normalcy. The best solution will come with a vaccine, estimated to take another 18 months. In the meantime, other new medical therapies may reduce anxiety.

Athreya at the Richmond Fed said government officials might also help by establishing new safety regimes aimed specifically at business sectors that have been hit the hardest.

He suggested, as one example, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) might publish a set of best practices for restaurants that could reduce the risk of new transmissions. Restaurants could then post a notice saying they have complied with the CDC guidelines.

"We need to have a regime in place, something credible, to give people confidence in communal consumption," he said.

—With assistance from Catarina Saraiva.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.