The coronavirus has forged a once-unlikely alliance between Donald Trump's Treasury Department and the central bank he often derided. The close embrace is resurfacing concerns about the independence of the Federal Reserve in the long run.

By openly urging Trump and Congress this week to spend more money fighting the pandemic, while promising to keep interest rates low, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell risks putting the central bank into a political box once the health emergency has passed.

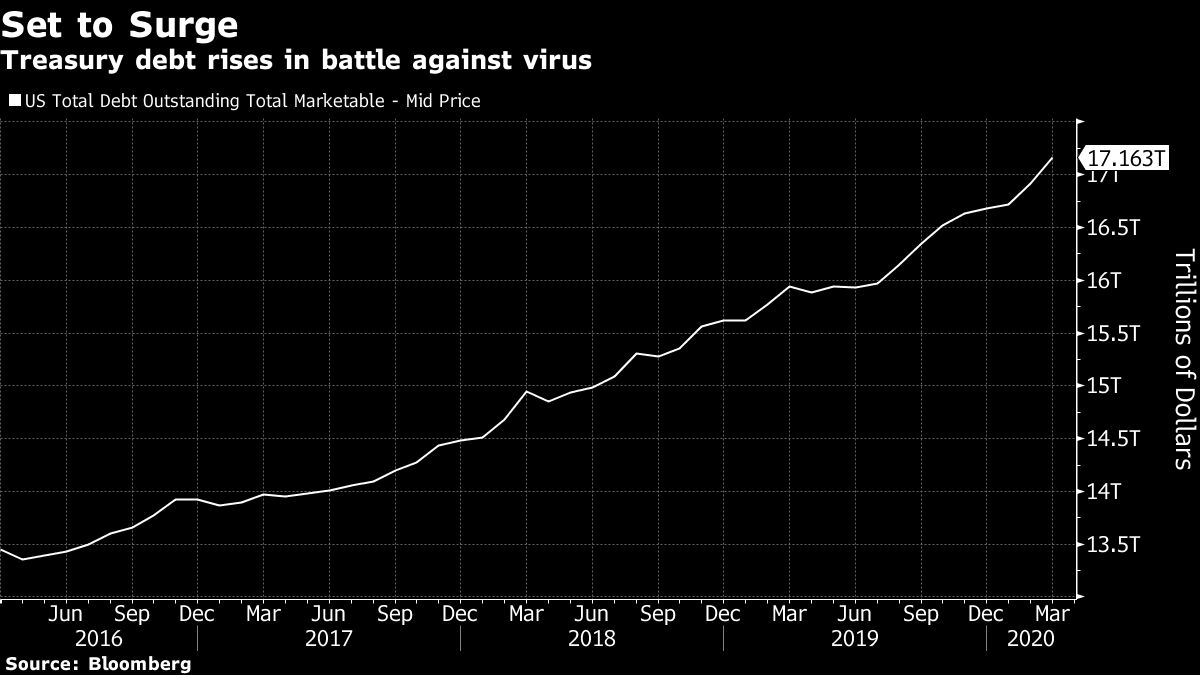

Government borrowing has skyrocketed during the crisis. The big worry is that Fed policy will end up being driven by the need to manage the costs of that debt—preventing the central bank from taking actions, like raising interest rates for example, that the economy might otherwise require.

"The Treasury and the Fed: Are they single, married, or divorced?" asks former chief White House economist Glenn Hubbard, now at the Columbia Business School. "We read articles that the Treasury secretary and the Fed chair get along. I think that's just super," he says. "But I'm much more interested in the institutional aspects. And I do worry a little there."

The problem is known by economists as fiscal dominance. In extreme cases, it involves central bankers providing the government with all the cash it demands. That historically has been a recipe for faster inflation—often a lot faster.

That's not a concern in today's slump. Most economists and investors see deflation as a greater threat, expect that to remain the case for quite a while, and welcome damage-limitation efforts by the Fed and Treasury—including the ramp-up in public debt.

But some financial market pros see reason to worry about tomorrow. "When we come out of this, we're going to have so much debt and so much demand," David Kelly, chief global strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, told Bloomberg Radio on April 24. "Once inflation gets going, people are going to doubt the ability of the Federal Reserve to corral that inflation."

With publicly-held Treasury debt set to rise from more than $17 trillion last month, even a small increase in interest rates can have a big negative impact on government finances.

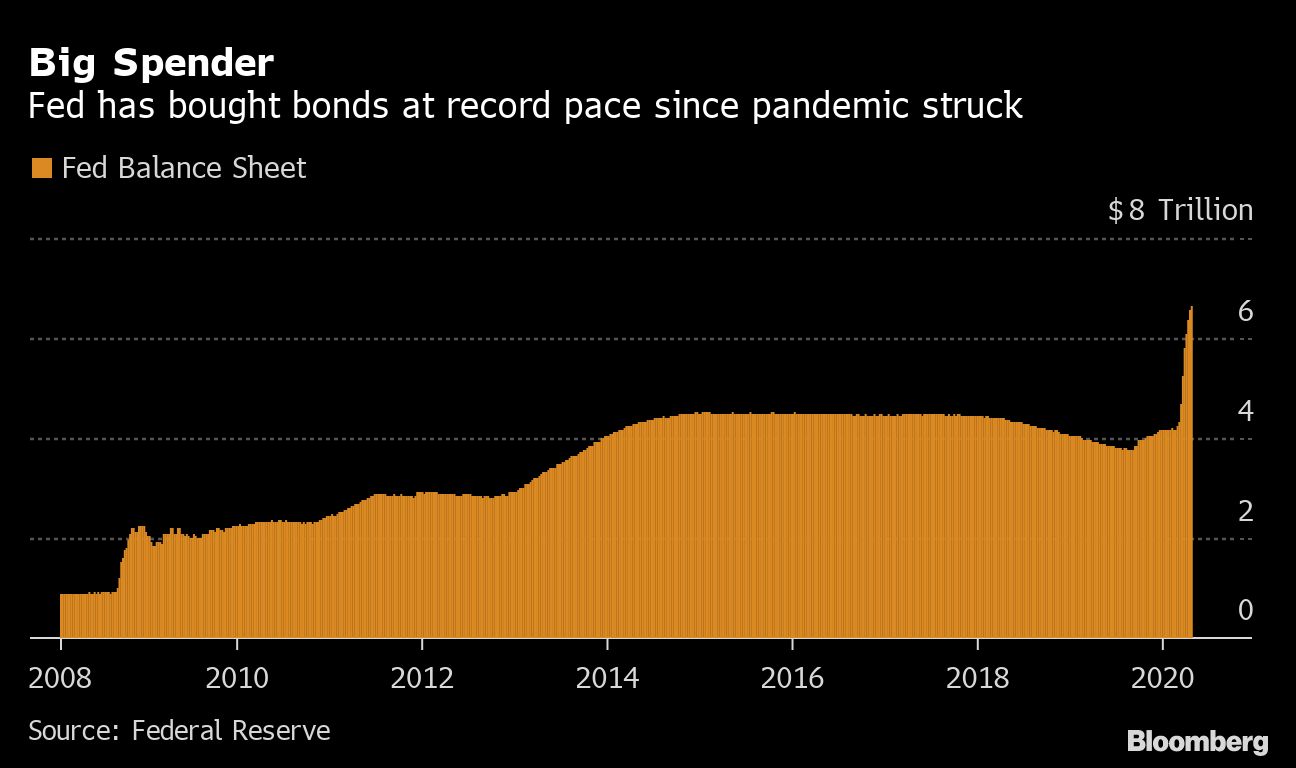

Besides working closely with Treasury to set up emergency loan programs for borrowers hard hit by the Covid-19 crisis, the Fed has also cut its short-term interest rate effectively to zero and embarked on a bond-buying spree. In addition, it may adopt a strategy known as yield-curve control, which would aim to cap rates on longer-term government debt.

'Historic' Change

Such policies help limit borrowing costs for the Treasury, as it racks up what's forecast to be a record budget deficit of about $3.7 trillion this fiscal year.

BlackRock Inc. senior portfolio manager Jeffrey Rosenberg sees parallels to World War II and its aftermath, the last time that government debt grew this large in relation to the economy. Back then, the Fed agreed to peg rates on Treasury securities—0.375 percent on bills and 2.5 percent on the 30-year bond—to help finance the war effort.

"What we've seen here is just an historic structural change in the relationship between the Federal Reserve and fiscal policy," Rosenberg told Bloomberg Radio last month. "This is all about securing the interest rate that the government will pay to fund the massive fiscal response that we've seen to fight the pandemic."

And that, rather than the "shape of the economic recovery," is likely to remain the key factor in setting rates, he said.

After World War II ended, it took the Fed until 1951 to free itself from the clutches of Treasury. Inflation at the time was running above 9 percent.

Former International Monetary Fund (IMF) chief economist Olivier Blanchard said that growing government debt might make the Fed "think a bit harder" about raising interest rates in the future. But he's not particularly concerned. "It really would take a total loss of independence because of a change at the top of the central bank for this to become a major issue," Blanchard said.

That's not so far-fetched. Powell's four-year term ends in February 2022, and Trump has shown a preference for trying to appoint political supporters to the central bank—though the president would first need to win re-election in November, of course.

With inflation below the Fed's 2 percent target for years, Powell and his colleagues would welcome some increase in price pressures. But that doesn't mean they can throw caution to the wind.

"There is a lot of liquidity that has been and is being created," former Fed vice chairman Alan Blinder said. "As the economy starts getting back to normal, one of the Fed's challenges will be how to withdraw that liquidity at a reasonable pace."

"I'm not so worried about inflation coming out of this episode, but it's not impossible," the Princeton University professor added. "Too much money chasing too few goods. There is something to the cliché."

—With assistance from Christopher Condon.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.