The coronavirus recession is generating winners and losers in corporate America, with cash-rich behemoths set to get bigger, while debt-heavy companies and the economy lag.

Slammed by the now-ending economic and social lockdown, a growing number of enterprises are filing for bankruptcy or closing up shop because they can't pay the bills. Others are downsizing even as they pile up more I.O.U.s, adding to already-record U.S. corporate debt.

The upheaval will act as a drag on growth, as highly leveraged companies are forced to divert resources from expanding their businesses to meeting creditor obligations.

"Higher debt burdens coming out of this are likely to slow recovery," said former Federal Reserve governor Jeremy Stein.

See also:

- A Tsunami of Loan Modifications Is on the Horizon

- Search for Solutions as the Tsunami Approaches

- How to Ride High on the Loan-Modification Wave

- A Shrewd Bond Maneuver

The shakeout, though, will give cash-rich corporate titans an opening to grab market share and extend their dominance as the economy gradually reopens. "The behemoths within the U.S. are going to have more market power," Nobel Laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz said.

Potential winners include the liquidity-laden FAANG stocks beloved by investors: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google-driven Alphabet. Big-box retailers Walmart and Costco Wholesale also could come out ahead. So, too, might retail farm store chain Tractor Supply.

Loser Lineup

Meanwhile, the losers already are lining up at the bankruptcy courts. Among them are such American mainstays as J.C. Penney, J. Crew Group, and Hertz. Small and midsize businesses that operate on thin profit margins are particularly vulnerable. While many have availed themselves of help via the government's Paycheck Protection Program, they still face daunting prospects adjusting to a world where the virus remains a threat.

"Business failures are going to be in the hundreds of thousands," said Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody's Analytics.

Winnowing out small firms would be a plus for larger, publicly traded companies, allowing them to grab a bigger piece of the profit pie. That may be one of the reasons why the stock market has performed so well relative to the dismal performance of the economy, said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Unemployment unexpectedly fell last month to 13.3 percent, from 14.7 percent in April, but was still more than triple the level that prevailed prior to the pandemic. Among companies cutting jobs: airplane maker Boeing and ride-hailing giant Uber Technologies.

Even before the crisis, many economists were becoming increasingly concerned about the rise of corporate leviathans that dominate industries and stifle competition. It's not only about tech, where Alphabet enjoys a more than 85 percent share of the global search-engine business. It's also about the now-ailing airline industry (Delta, United, American); drugstore chains (CVS, Walgreens); and even the consumer product in short supply early in the crisis, toilet paper (Georgia-Pacific, Procter & Gamble, Kimberly Clark).

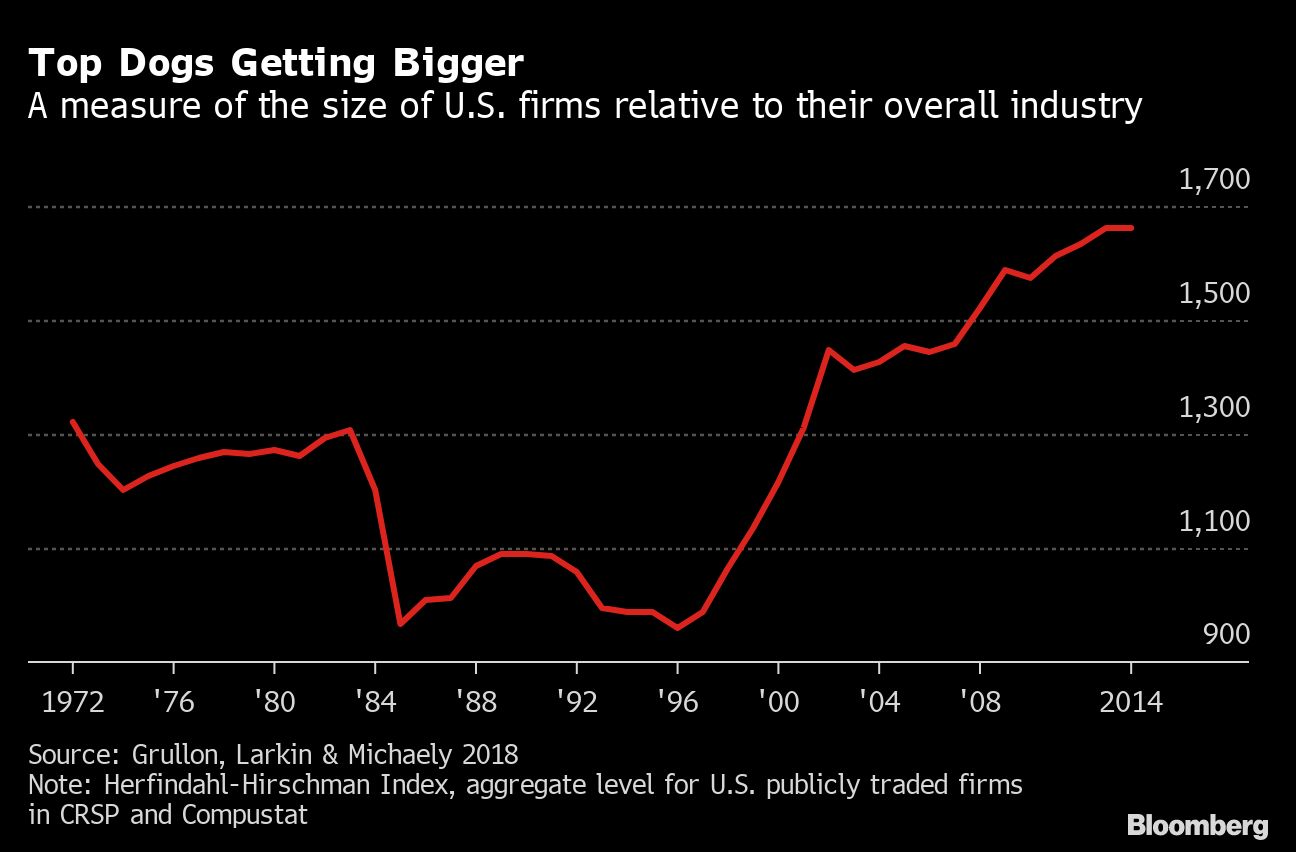

Overall, the market share held by the top players has increased in more than 75 percent of U.S. industries during the past two decades, according to a 2018 paper by Rice University professor Gustavo Grullon and fellow researchers.

That's being blamed for a variety of economic ills. In his 2019 book "The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets," Thomas Philippon, a professor at New York University's Stern School of Business, argues that a lack of competition leads to lower wages, less business investment, and slower economic growth.

More concentration also means a bigger risk of supply-chain disruptions. That's what happened in April, as the shutdown of some meatpacking plants hit by the coronavirus threatened the nation's food supply, forcing President Donald Trump to invoke emergency powers to open them back up. Three companies—Tyson Foods, JBS, and Cargill—control about two-thirds of America's beef, and the bulk of it gets processed in a few dozen giant plants. So even closing a small number of facilities was enough to call into question the availability of supply.

"The existing levels of concentration there have now been proven dangerous," said Barry Lynn, executive director of the Open Markets Institute think tank.

Recessions historically lead to market consolidation, as financially weaker firms are forced out of business. That could prove to be particularly true this time, given the unprecedented depth of the downturn and the large amount of debt many companies carried into it. In May alone, some 28 businesses reporting at least $50 million in liabilities sought court protection from creditors. That brought the total for the first five months of the year to 99 for companies of this size—the most for the period since 2009.

The toll might have been even greater if not for the Fed's Herculean effort to keep credit flowing to the economy via the capital markets. Through the first five months of 2020, companies issued more than $1.2 trillion in bonds, almost double the amount in the same period last year. From cruise-line operator Carnival to car-rental company Avis Budget Group, many corporations have raised billions of dollars despite doubts about their long-term viability.

Widespread Carnage to Come

Lazard Ltd. CEO Ken Jacobs does see trouble ahead for cash-strapped businesses even as economies begin to reopen. "The second wave likely starts sometime this summer for the companies that don't have enough money to make it through," said Jacobs, whose firm is working on some of the largest company restructurings in the world.

Edward Altman said he expects a record number of mega-bankruptcies this year, surpassing the previous high of 49 in 2009 for companies with liabilities greater than $1 billion. Defaults on junk bonds also will spike, the professor emeritus at NYU'S Stern School added.

"It's not only the impact of Covid-19, which is of course the primary reason, but also the enormous amount of debt that had been building up in the economy prior to it," said Altman, who developed a widely used method called the Altman-Z-Score for predicting business failures.

The carnage is likely to be more widespread among small firms that lack access to the capital markets and depend on their own resources and the banks for financing. An April survey of small businesses by a group of economists including the University of Chicago's Marianne Bertrand found the median respondent had more than $10,000 in monthly expenses and less than one month of cash on hand.

"Market concentration should increase significantly, which undermines workers' ability to negotiate their wages, as big companies with access to capital markets take over from the small independent shops that are getting wiped out," said Megan Greene, a senior fellow at Harvard University's Kennedy School.

To protect themselves from takeovers, some corporations are adopting so-called poison pills, which generally allow investors to acquire additional shares if an unwanted suitor takes a significant stake in the company. That includes Office Depot, which last month announced plans to lay off about 13,000 employees, and Oklahoma City driller Chesapeake Energy, which is preparing a potential bankruptcy filing.

Accelerated Shift in Wealth and Commerce Toward Big Business

Progressive Democratic lawmakers Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York also have weighed in, pushing a bill that would ban many corporate mergers while the coronavirus crisis persists. The proposal faces extremely long odds in the Republican-controlled Senate and with Trump.

Even before the crisis hit, big tech companies were facing increased scrutiny from antitrust regulators. While that could inhibit them from making overt moves toward consolidating their market power, it didn't stop Amazon from recently looking into buying driverless-vehicle startup Zoox.

And not every economist is convinced that increased market concentration is all that bad. In a paper last year, Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor David Autor and fellow researchers argued that so-called superstar firms are prospering because they're more productive than their rivals.

No matter the reason, the rich seem poised to get richer because of fallout from the pandemic. "There's an accelerated shift in wealth and commerce going on from small businesses to big businesses," former deputy Labor secretary Seth Harris said.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.