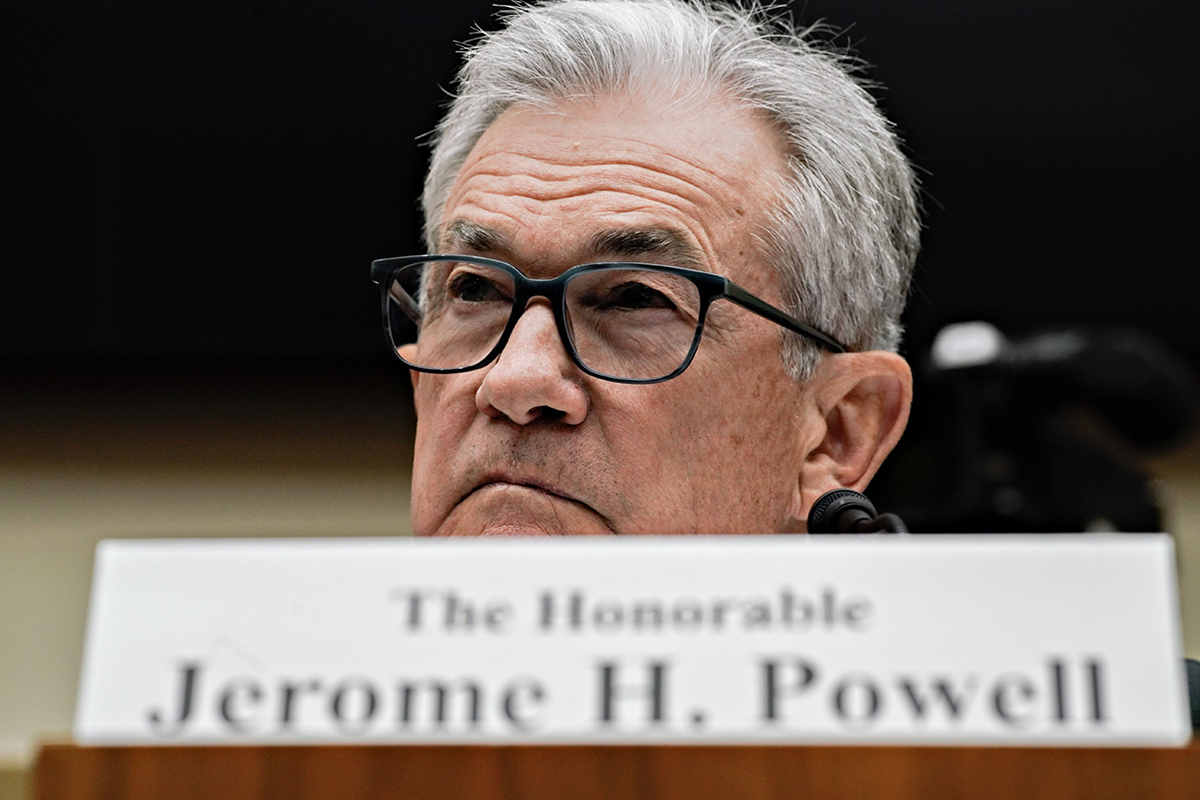

Fed Chair Jerome Powell

Fed Chair Jerome Powell

Jerome Powell faces heightened pressure this week from Democrats who want interest rate cuts to keep the economy humming in an election year and Republicans who want him to scrap a plan to boost bank capital.

The Fed chair heads to Capitol Hill on Wednesday and Thursday for his semiannual testimony before Congress, two years after the central bank began its aggressive battle against surging inflation. With the economy powering along and inflation inching toward the Fed's sweet spot, Powell will make the case for why officials are in no rush to lower rates.

Recommended For You

Meanwhile, some Democrats who've tried to avoid bullying the Fed are growing impatient.

"The pressure usually comes from one side or the other, and this time it's probably going to be coming from the Democrats because the Fed has drifted more hawkish this year," said Marc Sumerlin, founder of Evenflow Macro in Washington. "They don't want the economy to roll over accidentally because when it happens, it happens quickly. To the Democratic Party, that's a massive risk."

The Fed raised rates rapidly in 2022 and 2023, and officials have held them at a two-decade high since July. The central bank's preferred inflation gauge rose 2.4 percent in January from a year earlier, down substantially from a peak of 7.1 percent in 2022 but still above the Fed's 2 percent goal.

That inflation progress has prompted calls from some lawmakers to start dialing back borrowing costs.

In a January 30 letter, Senator Sherrod Brown urged Powell to cut rates "early this year," arguing that high rates are hurting small businesses and putting homeownership out of reach for many Americans. That missive from the Senate Banking Committee chair, an Ohio Democrat who is running for re-election this year, could give cover to other committee Democrats who want to press Powell on rates.

Maryland Democrat Chris Van Hollen, in an interview last week, said the Fed needs to focus on housing costs "and taking actions necessary to make things more affordable for more Americans."

"Right now those high interest rates are actually increasing costs for families because one of the big parts of costs for families is housing," Senator Elizabeth Warren, a persistent Powell critic, said in a Bloomberg Television interview. "It's time to get those interest rates down."

Powell will be testifying after a busy stretch of public remarks from Fed officials, including his own interview on CBS's 60 Minutes. The resounding message: Policymakers need more evidence to be sure inflation is heading toward their target—and, once they get there, they're likely to bring rates down gradually.

Officials don't want to cut rates too soon and reignite price pressures, a mistake that forced the Fed in the 1970s to raise rates much higher, ultimately triggering a painful recession.

Capital Rules

Meanwhile, Republicans will use Powell's appearance to grill him on the Fed's proposal to ramp up capital requirements for big banks by almost 20 percent.

The plan, from Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr, has drawn intense criticism from GOP lawmakers and the banking lobby. Changes to it are likely forthcoming, and Powell has signaled the final version will need broad support from the Fed board.

"The biggest thing before the Fed is not a quarter point this way or that, but this larger view of capital for banks," said Patrick McHenry, a Republican from North Carolina and chair of the House Financial Services Committee. "The Barr approach here is rife with politics, lacking in strong economic analysis, and is not good for American competitiveness."

Powell's testimony is coming near the one-year anniversary of Silicon Valley Bank's failure, which could also prompt questions about the Fed's emergency lending program for banks, set to close on March 11.

Election Year

Powell has repeatedly said the looming election plays no role in policy decisions, but some Fed watchers worry rate cuts this year—investors are betting the first reduction will come in June—could be perceived as the Fed giving a boost to Democrats.

"Coupled with a better-than-expected economic performance in the first half of the year and relatively sticky inflation, the campaign season may convince the Fed to stay on hold until after the election," Stephen Stanley, chief U.S. economist at Santander U.S. Capital Markets LLC, wrote in a note to clients last week.

McHenry cautioned against lawmakers weighing in either way.

"I know that folks on the populist right and populist left think that they can tinker with interest rates to their political benefit, but I think it's a huge mistake," he said. "Especially in an election year. It shows exactly why Congress has outsourced monetary policy."

Powell may also face questions about the Fed's plans for its massive portfolio of assets, which it's been shrinking for the past couple years, and about the huge amounts of interest it's paying to banks that park reserves at the Fed. The Fed's expenses now exceed earnings on those assets, forcing the Fed to post its biggest operating loss ever last year.

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.