If it's not one coast, it's the other.

If it's not one coast, it's the other.

Workers at port facilities on the West Coast went back to work early this month as members prepared to vote on a settlement of a bitter dispute that led the International Longshoremen Workers Union to shut ports there for eight days earlier this fall. Now time's running out on a Dec. 30 strike deadline set in September by the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA), which represents dockworkers on the East Coast and Gulf Coast.

The December deadline was a postponement of the original strike deadline of Sept. 30, but the ILA and the U.S. Maritime Alliance (USMX), which represents port operators, reportedly have not made much progress in negotiations since then, which could lead to a shutdown of ports from Maine to Texas, including New Orleans, Houston, Savannah, New York/New Jersey and Portland.

Recommended For You

Atlantic ports handle 40% of all waterborne shipping in the United States, moving cargos worth some $437 billion a year, according to the Department of Transportation.

Gary Lynch, global leader for risk intelligence and supply chain resiliency solutions at Marsh Risk Consulting, says many "midrange" businesses that supply larger companies with parts, supplies or finished retail goods may be caught unawares by the looming strike deadline. "A lot of companies assumed that the labor issues had been resolved back in September when the strike deadline was put off," he says.

A Marsh study authored by Lynch says a strike that closed Atlantic and Gulf ports would impact "a cross section of industries, including electronics, machinery, clothing, retail, pharmaceutical, construction, food and beverage, and automotive businesses."

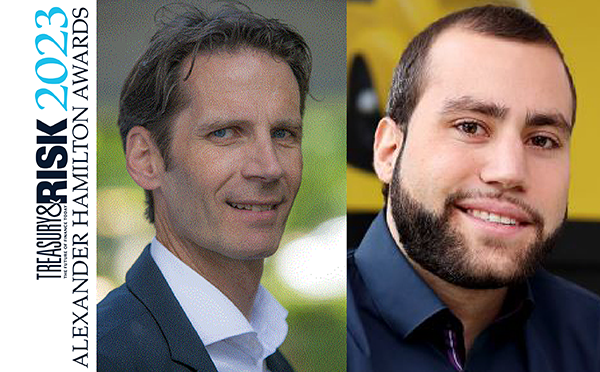

Lynch, pictured at left, says the possibility of back-to-back port strikes on both coasts "demonstrates why global businesses must be prepared for powerful and possibly crippling disruptions" to supply chains that don't involve destruction of goods but the inability to deliver them.

Lynch, pictured at left, says the possibility of back-to-back port strikes on both coasts "demonstrates why global businesses must be prepared for powerful and possibly crippling disruptions" to supply chains that don't involve destruction of goods but the inability to deliver them.

When it comes to supply chain issues, Lynch says, many companies still think in terms of physical losses of goods and natural disasters. "They need to be prepared for these kinds of things too," he says.

Lynch notes that every day a port is closed by a strike can cause supply disruptions that take an average of eight days to resolve. And if a company plans ahead and stocks up on needed supplies in response to a strike threat and then there's a settlement, the company can be left with too many supplies or having too many goods on hand ready to ship. In some cases, the goods can be perishable, for example agricultural or pharmaceutical cargo.

Insurers offer what is called voyage frustration insurance and trade disruption insurance. Lynch says that while these policies are available, for a price, even on the eve of a possible strike, the problem is low limits. "Usually the limits are set somewhere around $25 to $40 million, which is not going to help most big companies that much," he says.

In addition to stockpiling supplies, companies should be lining up alternative port facilities, for example in Canada or on the Great Lakes or, where possible, booking air cargo capacity, Lynch says. He notes that one problem with shifting ports is that to gain access to an alternate port, "you have to guarantee a certain cargo volume." A contracting firm would be responsible for that volume even if a strike never occurred.

Companies' alternatives are limited by drought conditions that are threatening the Mississippi River ports of Louisville and Memphis, where companies ordinarily could have switched to barge shipments. River barge traffic has been sharply curtailed though, because of unusually low water levels.

While a prolonged strike on the East Coast is not likely to lead companies to shift permanently to other ports or other means of transport, Lynch says it could add impetus to a recent trend to "source locally and sell locally." This trend has led some U.S. companies to shift production back to the U.S., as Apple recently announced it plans to do with some products currently manufactured in Asia.

Meanwhile, Lynch says the latest threat to U.S. industries' global supply chains should encourage companies that haven't done so already to focus on making their supply chains "more flexible" and more diversified.

For previous coverage of supply chain issues, see Sandy Brings Big Business Interruption Losses, Supplier Finance Advantage and Supply Chain Insurance Woes.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.