China devalued the yuan by the most in two decades, a move that rippled through global markets as policy makers stepped up efforts to support exporters and boost the role of market pricing in Asia's largest economy.

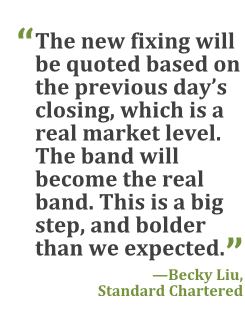

The central bank cut its daily reference rate by 1.9 percent, triggering the yuan's biggest one-day drop since China ended a dual-currency system in January 1994. The People's Bank of China (PBOC) called the change a one-time adjustment and said its fixing will become more aligned with supply and demand.

Chinese authorities had been propping up the yuan to deter capital outflows, protect foreign-currency borrowers, and make a case for official reserve status at the International Monetary Fund. Tuesday's announcement suggests policy makers are now placing a greater emphasis on efforts to combat the deepest economic slowdown since 1990 and reduce the government's grip on the financial system.

Chinese authorities had been propping up the yuan to deter capital outflows, protect foreign-currency borrowers, and make a case for official reserve status at the International Monetary Fund. Tuesday's announcement suggests policy makers are now placing a greater emphasis on efforts to combat the deepest economic slowdown since 1990 and reduce the government's grip on the financial system.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to Treasury & Risk, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited Treasury & Risk content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Thought leadership on regulatory changes, economic trends, corporate success stories, and tactical solutions for treasurers, CFOs, risk managers, controllers, and other finance professionals

- Informative weekly newsletter featuring news, analysis, real-world case studies, and other critical content

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical coverage of the employee benefits and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, PropertyCasualty360 and ThinkAdvisor

Already have an account? Sign In Now

*May exclude premium content© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.