Once upon a time, employees who were dissatisfied with how management treated them might respond by organizing, filing a grievance, or suing. If they were really frustrated, they might refuse to sign the warning notice or performance appraisal form that was presented to them in protest.

Once upon a time, employees who were dissatisfied with how management treated them might respond by organizing, filing a grievance, or suing. If they were really frustrated, they might refuse to sign the warning notice or performance appraisal form that was presented to them in protest.

Nowadays it is not uncommon for disgruntled employees to push the boundaries of behavior much further, even to the point of killing supervisors or managers. From June 2015 through September 2016 the following tragedies occurred:

-

Jason Yanko, 40, an operations manager in Texas was shot several times by an employee he was in the process of firing. Investigators identified 25 spent shells at the scene. Yanko's body was found clutching the termination paperwork in his hands. The employee was later sentenced to life imprisonment for Yanko's murder.

-

Ward R. Edwards, 49, a manager in Indiana, was killed in a conference room by an engineer who reported to him. After shooting Edwards, the man took his own life. As is usually the scenario with deadly violence, the incident threw the workplace, with a reported 1,100 workers, into chaos.

-

Andrew Little, 55, a supervisor at a landscaping company in Florida, was shot to death. The employee charged with Little's murder reportedly felt he was being disrespected, was not being compensated fairly, and had prior run-ins with Little and others, but mainly with Little. According to the police report, the suspect ran to his vehicle after the shooting and retrieved a baseball bat before being arrested. While in jail awaiting trial on Little's murder, he was charged with a second felony.

-

Air Force Lt. Col. William Schroeder, 39, commander of the 342nd Training Squadron in Texas, was murdered by a technical sergeant who was facing discipline. As he struggled to gain control over the shooter who was brandishing a glock, Schroeder valiantly warned others in the area to run. Bullets struck Schroeder in the arm and the head. The shooter then committed suicide.

-

Mike Dawid, 35, a Texas manager, was killed by a former employee who returned to the workplace two weeks after his termination. Flying glass caused by shotgun blasts injured employees who were working in the area at the time of the shooting. The ex-employee then killed himself.

-

Sandra Cooley, 68, and James Zotter, 44, supervisors at a factory in Tennessee, were killed by Ricky Swafford, 45, a long-term employee who they had been meeting with. Swafford became upset, left the meeting, and returned to shoot them before killing himself. Zotter had just been promoted to supervisor a week before his murder.

Deadly Workplace Violence: A Growing Epidemic

Workplace violence even occurs in the most peaceful of communities. On February 25, 2016, a disgruntled worker equipped with a rifle and a glock murdered three co-workers and shot 14 more people at Excel Industries in the small town of Hesston, Kan. He also fired at a first responder but missed. The first responder fired back, killing the shooter and putting an end to the carnage.

While domestic violence is sometimes the underlying cause of workplace violence, it is most certainly not the only reason. In the Hesston tragedy, the shooter had been served with a domestic violence restraining order shortly before he embarked on his killing spree.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), “Homicide is currently the fourth-leading cause of fatal occupational injuries in the United States.” OSHA defines workplace violence as “…any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide.”

OSHA estimates that approximately 2 million workers experience workplace violence annually, but the number could be even higher since many episodes go unreported.

“It is impossible to overstate the costs of workplace violence, because a single incident can have tremendous repercussions,” states Angelo J. Gioia, an insurance executive with 40 years expertise. Gioia is a nationally recognized professional liability expert, publisher, author, and founder of the Professional Liability Underwriting Society (PLUS) and AgentsofAmerica.org.

Claims arising from workplace violence can involve a wide range of insurance policies including business interruption, property, employment practices, liability, director and officer omissions, health, life, worker's compensation, and more.

Gioia explains that “while having insurance can address some of the economics relating to the loss, it is not the solution to the problem at hand. Insurance companies can only react and, at best, can only provide a mechanism that provides both a defense and indemnity payment if there is a covered loss.”

Strategies to Prevent Workplace Violence

Reducing the risk of workplace violence begins and ends in the workplace with a company's leadership. “The first line of defense is the employer who has a duty, financial responsibility and legal obligation in creating a safe work environment,” said Gioia.

Employees who kill tend to do so because they feel powerless and need to redistribute the balance of power. What can be done to prevent these scenarios?

Felix P. Nater, CSC of Nater Associates, Ltd., is an authority on workplace violence prevention and believes that employee-on-employee workplace violence can be anticipated if one focuses on red flags and cues, and acts on them in a timely and proper manner rather than ignoring or missing them. “Merely having a workplace policy is not good enough without a program supporting the prevention effort. It has to be a living document that employees trust and have confidence in, not one that is used to discipline as a reactionary tool,” opines Nater.

Nater, a retired postal inspector, was one of several colleagues responsible for recommending, developing, and implementing prevention and security strategies in the postal service in the 1980s and 1990s. He asserts that the appropriate perspective to take is not “if” it happens but “when” it happens. “If” implies a reactionary response, versus “when,” which anticipates the possibilities, says Nater.

“Workplace violence prevention as it relates to employee-on-employee threats is manageable and therefore is preventable,” Nater explains. Employers have an opportunity to observe behaviors in their employees before they erupt into verbal or physical hostility. Nater feels that a first line supervisor plays a key role in stopping workplace violence in its tracks.

It is necessary for supervisors to act on cues of budding violence such as verbal abuse or bullying, which should not be tolerated. It could also be early signs of future conflict, which may continue on to include more bullying and even physical abuse if left unaddressed. According to Nater, “Supervisors must not rush to judgment. They must be impartial in identifying contributing factors and root causes before applying the broad brush of discipline. Leadership plays a key role in counseling and guiding employees toward appropriate behavior.”

Nater believes that supervisors must also be cognizant of what is occurring in the workplace with their employees at all times. “In some cases, a frustrated employee may begin thinking about acting on rage. Supervisors, of course, cannot read every deviant thought an employee may have, but they can certainly take action when they observe aggression or inappropriate behaviors,” states Nater.

There are usually signs of problems beforehand and a situation akin to a rubber band being pulled and pulled until it finally snaps. Part of the problem is a lack of appropriate training and supervision to spot the red flags and cues.

“We have fallen woefully short in this country because supervisors are in many cases promoted without appropriate training in how to be a supervisor of people. This includes recognizing warning signs employees may be transmitting and then failing to respond swiftly and appropriately, and not being held accountable when they fail to do so,” Nater opines.

When referring to this lack of training, Nater says, “It is one thing to be a great salesperson or help desk specialist. Being promoted to a sales or help desk supervisor involves an entirely different scenario and requires a different skill set where people management is concerned.”

One strategy that can be immensely helpful is what Nater calls a robust, agile, proactive (RAP) mindset that helps management avoid being caught by surprise by unacceptable actions. He also believes the best way to manage today involves approaching employee safety from a holistic perspective with what he calls “care and concern” for the workforce.

There are many rewards for those who engage these skills. One includes fostering an environment where employees will alert supervisors to concerns about colleagues and changes in behavior or odd random acts because they trust the policy and believe in the program. However, some may be reluctant to report a colleague.

“Before you can expect an employee to come forward and report troublesome behavior from a co-worker, there must be trust and confidence that the information will be handled appropriately and responsibly without fear of retaliation or disciplinary action before resolution of the issue,” says Nater. A mishandled case can affect the process indefinitely.

Employees who observe a co-worker bullying someone else may fear experiencing the same behavior if they report the bully.

“The buck stops squarely at the first line supervisor's desk. If the employee trusts the supervisor, he or she may not feel so apprehensive about dropping a dime. If the report results in retribution, the employee and all others around him or her will probably not speak up again in the future,” says Nater.

Avoid Zero-Tolerance Policies

It is important for all involved to recognize that bullying, harassment, assault, and worse happen with increasingly regularity. Connecting the dots is key to managing aggression, says Nater, who feels that employers must take responsible action in providing a safe, secure, and productive workplace.

“We do this by first creating appropriate policies, training supervisors on what their role is and should be, enforcing existing policies fairly with an attempt to correct the situation reported, and keeping all those involved informed. In short, think program development and program management in reinforcing the long-term prevention effort,” says Nater.

Nater does not advocate a “zero tolerance” policy, which emphasizes discipline. It is too rigid and reactive and takes the focus off of implementing strategies to develop appropriate behaviors within the workforce.

Janette Levey Frisch, Esq., an attorney with more than 20 years of legal experience and the founder of the EmpLAWyerologist firm agrees zero tolerance is not the answer and questions its effectiveness.

“Zero-tolerance policies usually mean you want to stop something that has already occurred and that you think is very bad, and want to take a public stand that something is being done to address it,” she explains. This is simply not the best position to take.

While zero tolerance is not the answer, she does believe there is a better approach. “Employers should consider proactive policies and solutions rather than rigid, reactive, or knee-jerk responses to employee conduct,” she advises.

The Employer's Legal Duty to Provide a Safe Workplace

In accordance with governing federal law, employees are entitled to safe working conditions under Section 5 of the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act (the OSH Act) of 1970. OSHA is charged with various responsibilities including administering and enforcing the OSH Act and engaging in educational activities intended to promote employee health and safety goals.

Stephanie Ross, 24, was a social service coordinator employed by Integra Health Management (“Integra”) in Florida. Part of her job duties required Ross to make home visits to her employer's clients, including one severely mentally ill man who had a violent criminal history. After a few meetings, Ross disclosed in her written case records that she felt uncomfortable being alone with him. In December 2012, the man stabbed Ross to death outside of his home.

OSHA conducted an investigation into Ross's death and issued two serious citations and assessed penalties totaling $10,500 against Integra for failing to report Ross's death to OSHA and for failing to protect employees from workplace violence hazards. (Employers are required to report any on-the-job fatalities to OSHA within eight hours of learning of the event.) A judge for the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission reviewed the case and agreed with OSHA's investigators that Integra failed to protect Ross.

Health care workers are particularly susceptible to workplace violence. Following Ross's murder, OSHA announced it would step up its inspection and enforcement activities in the medical industry to focus on workplace violence amongst other safety and health risks.

Stuart M. Silverman, Esq. of Stuart M. Silverman, P.A., says there are several theories “a claimant could bring that could easily trigger coverage and a duty to defend” on the employer's part following an episode of workplace violence. These include negligent hiring and negligent supervision causes of action. There are key differences between them.

“Negligent hiring focuses on the employer's duties prior to the time the individual begins working, whereas negligent supervision focuses on actions of the employer following any decision to hire,” he explains. There are ways to mitigate the chances of these types of lawsuits.

Silverman believes the greatest opportunities for an employer to reduce the risk of workplace violence and any subsequent litigation occurs at the pre-employment and termination stages. Implementing the appropriate strategies lessens the chances of both violence and litigation says Silverman.

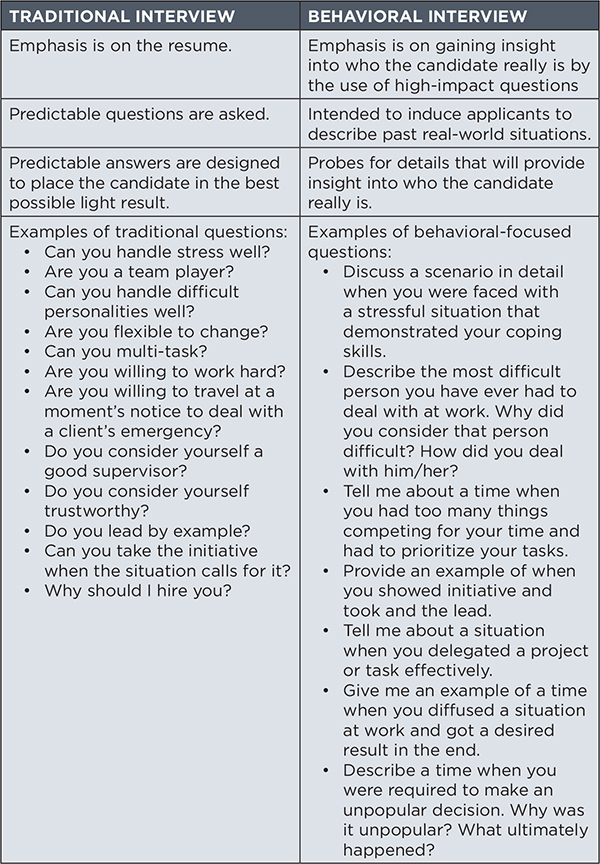

“Employers must be careful what dangers they let in the door to their employee family and how they get that danger out the door without causing harm to the family,” he adds. “It is much easier to simply not introduce a future bully into the equation. Use behavioral-based interviewing techniques—a hiring process that helps employers identify applicants who are potential future bullies during the recruitment stage. Bypass that person. Select someone else or go back to the drawing board and start again.”

Behavioral-based interviewing is a powerful tool that can help employers identify the candidate who possesses the appropriate skills, knowledge, and behaviors required to perform the job. “This mode of interviewing is very different and more effective than traditional interviewing techniques,” Silverman explains.

As an added bonus, behavioral-based interviewing is by definition legally compliant because it focuses exclusively on asking questions dealing with the core technical skills, knowledge, and experiences, as well as desired behaviors to perform the job. It does not delve into asking questions that focus on unnecessary, irrelevant, and illegal matters.

Terminations

For terminations, there are many steps employers can take to reduce the risk of employment practice liability claims and workplace violence such as:

Allow the employee to save face by scheduling the termination meeting at a place far from prying co-workers' eyes and ears. Avoid embarrassing the employee, and do not publicly terminate the employee.

Designate a person with strong human relations skills to conduct the employer's terminations. State the facts carefully, and avoid arguing with the person about the merits of the termination.

Have a plan in place regarding severance or benefits. Providing the employee's final paycheck with some severance can help reduce the potential for violence.

The more actions the employer takes to anticipate any problems before they fester and erupt into violence, the better.

“It is amazing that companies focus so much on the questions they cannot ask in the pre-hire stage and little to no focus on the termination stage. These days, the life you save may very well be your own or that of one of your valued colleagues,” Silverman concludes.

Keys to Hiring the Right Talent

The aftermath in the wake of deadly workplace violence can be extreme. In addition to the loss of life and the physical and psychological trauma it causes, there are the high costs associated with defending any resulting lawsuits, extreme disruption to the workplace, negative press, loss of goodwill, employee turnover, decreased employee morale, and more.

Minimizing the risk of workplace violence begins at the start of the working relationship. Take the time to conduct an effective interview. Do not ask questions on the spot. Develop behavioral-based interviewing questions. This method is based on the concept that the way an applicant behaved under similar circumstances in the past is a good indicator as to how he or she will behave in future.

The following grid highlights the differences between a traditional versus behavioral based interviewing line of questioning.

————————–

Kathleen M. Bonczyk is an attorney, former human resources executive, activist, and founder of the Workplace Violence Prevention Institute. To learn more visit www.kathleenbonczykesq.com.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.